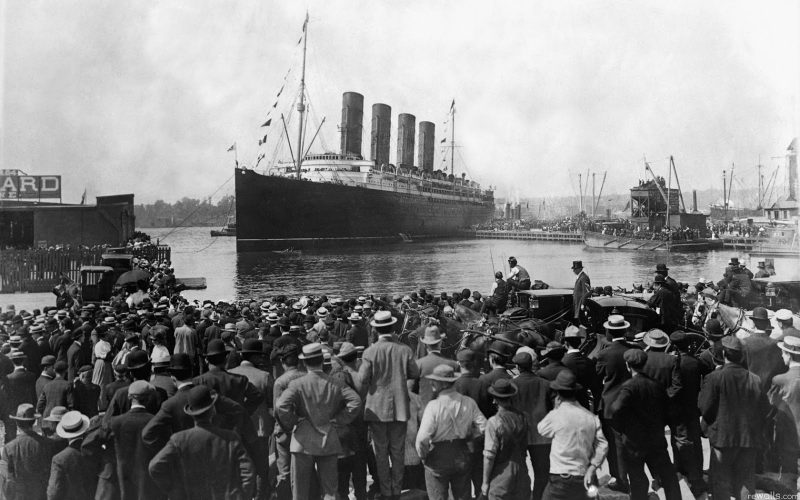

The White Star Line had been using the port of Southampton, on the south coast of England, as a major, and mainly transatlantic, port since 1907. However, the existing dock areas would not be large enough to accommodate the new Olympic-classliners, so a new, and much larger dock covering 16 acres and dredged to almost forty feet was constructed.

Named the White Star dock, unsurprisingly, there were three services a week to New York departing from it. Titanic’s sister ship, Olympic, had made her own trouble-free maiden voyage to New York in 1911, under the command of her then master Captain E.J. Smith. But now it was Titanic’s turn, although hers would involve much, much more drama.

As the gleaming Titanic awaited departure early on the morning of 10th April 1912, the members of the crew who hadn’t been on duty overnight began to arrive from all over Southampton. Some were already aboard, after all, the ship needed power at all times, and there would have been a skeleton crew aboard to provide steam, electric and heat. This skeleton crew also needed feeding, so some of the victualling crew would be aboard to provide it, adding again to the list of crew already aboard.

Due to a disruptive coal strike that had spread throughout the United Kingdom, many ships were laid up due to the lack of fuel, and consequently, over 17,000 men were left without work in Southampton alone. Even Titanic was indirectly affected by the strike: she had to top-up her own coal bunkers with coal acquired from other IMM vessels laid-up in Southampton, including, White Star’s Oceanic II and Majestic, and the American Line’s New York, Philadelphia, St. Louis and St. Paul.

Indeed, some of these vessel’s passengers were actually diverted to Titanic, as their own crossings were cancelled. To be working on a brand new ship that was the last word in luxury was almost compensation enough for being unemployed for those long, hard weeks, and spirits were very high. For every five crew members that were aboard Titanic, four of them hailed from Southampton, and nowhere would her loss be felt more than in the close-knit working-class areas of the city.

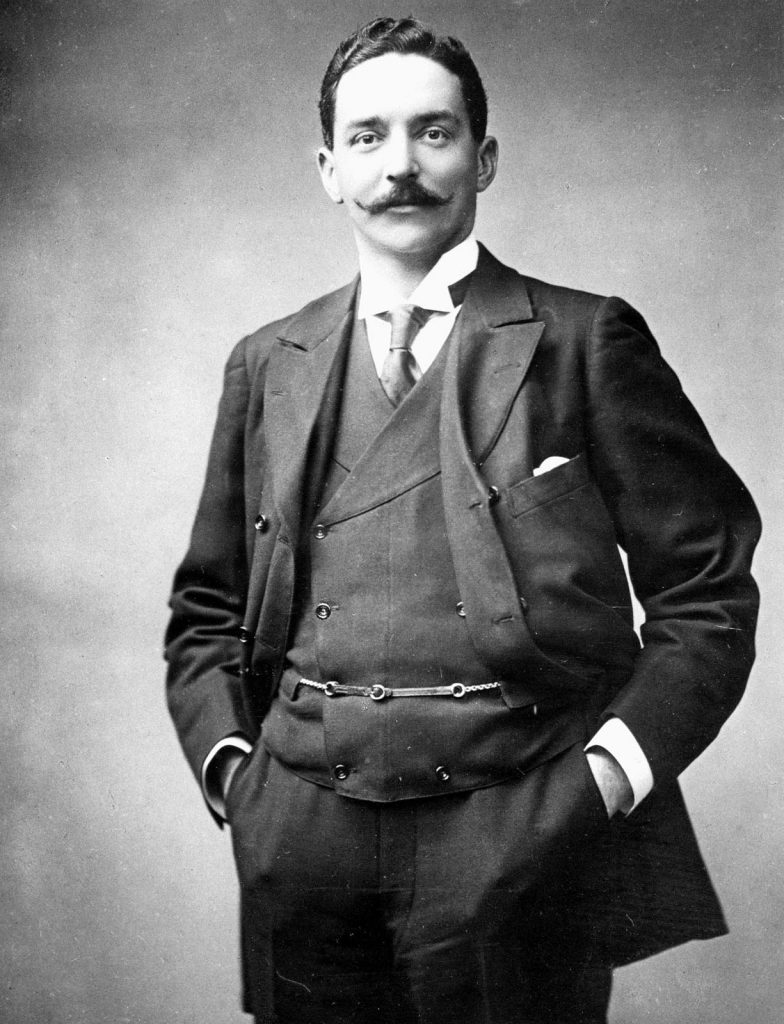

The White Star Line’s Bruce Ismay had stayed overnight at the South Western Hotel in Southampton, which overlooked the White Star dock, and therefore Titanic too. Although they were not passengers on the Titanic, his wife Florence and his children Evelyn, George and Thomas came aboard for a personal guided tour of the liner on the morning of departure.

Also present, constantly accompanied by his notebook, was Thomas Andrews, together with nine men from Harland and Wolff. These men were the highly skilled guarantee Group, aboard the ship to tend to any teething problems that might arise on the maiden voyage to New York.

At about the same time as the crew began to stream aboard, looking for their berths and their workstations, some with more success than others, the Boat Train was leaving London’s Waterloo Railway Station bound for Southampton, 80 miles distant. Aboard this train were some of the second and third class passengers, and upon its 9.30am arrival at Southampton Docks, all of these passengers were transferred straight onto the ship.

Whilst all of this activity and preparation was taking place, two of the starboard lifeboats, No. 11 & No. 15, were lowered under the supervision of officers Harold Godfrey Lowe and James Paul Moody to satisfy the Board of Trade’s Captain Clark, who was aboard under the Merchant Shipping Act to clear Titanic as an emigrant vessel.

He also had to see that systems such as freshwater supply, food stowage and crew and passenger accommodation were of a satisfactory standard. He also had to ensure that Titanic had enough coal aboard for her forthcoming voyage. He signed the ‘Report of Survey of an Immigrant Ship’, confirming the coal and lifeboat inspections.

The time was fast approaching midday, Titanic’s departure time.

The maiden voyage would soon begin.