The shipbuilding company of Harland and Wolff stands on Queen’s Island, in Belfast’s River Lagan, and was built on land reclaimed from a river-straightening scheme undertaken between the years 1841 – 1846. The company’s roots were initially sown in 1853, when Robert Hickson and Company opened a shipbuilding yard on the island, building iron-hulled ships.

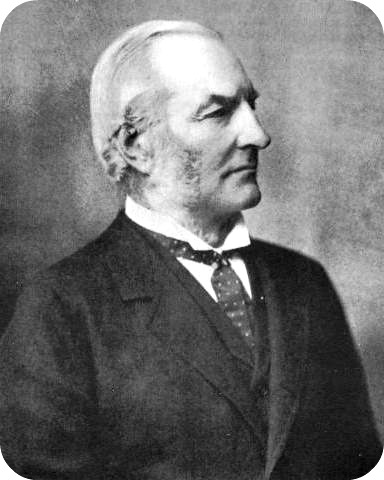

The following year, Hickson’s took-on one Edward James Harland as the shipyard’s General Manager. Harland had served his apprenticeship with Robert Stephenson and Company, and was vastly experienced in marine engineering, despite only being the relatively tender age of 23!

Four years later, Edward Harland bought the yard from his employer for £5,000, with financial help coming from one G.C. Schwabe of Liverpool. Schwabe’s nephew, Gustav Wilhelm Wolff had been Edward Harland’s personal assistant, but in 1861, Wolff ‘came on board’ as a partner, although it would be a further year before the company would actually trade under the name of ‘Harland and Wolff’.

In 1870, Harland and Wolff built their first White Star Line-owned vessel, Oceanic, which bore the hull number 73, and over the years, they built more than 70 vessels for them, quite a happy union for both parties.

Titanic’s chief designer, Thomas Andrews was a managing director at Harland and Wolff, and also head of the draughting department, responsible for producing every drawing for every part of the ship. He would later be on Titanic’s maiden voyage, almost continually writing down notes in a book which he always carried around the ship.

These notes were used to provide Harland and Wolff with alterations, suggestions and improvements to Titanic and Olympic, and the yet to be built Britannic. These notes were not a list of errors and problems as such, but more a list of refinements and tiny bits of detail that would allow Harland and Wolff to ensure that these already amazing superliners really were the last word in complete ocean-going luxury.

The ships were built on what is known as a ‘cost plus’ basis, which basically meant that all of the bills for materials and labour were passed on to the White Star Line, with Harland and Wolff’s profit margin added on.

Ships were increasing in size at an incredible rate around the turn of the century, and to ensure that they could accommodate these larger vessels, Harland and Wolff had constructed larger docks together with bigger slipways.

The builders of the Forth Rail Bridge near Edinburgh in Scotland, Sir William Arrol and Company Ltd, of Glasgow, were brought in to construct a huge new gantry, the Arrol Gantry, that had been specially designed by the shipyard’s own staff. At 840 feet long, by 240 feet wide, it could accommodate two Olympic-class liners side by side. Titanic and Olympic are pictured here, with Olympic to the right, the hull appearing to be nearing completion.

Harland and Wolff at about this time also built two tenders, Nomadic and Traffic, to be used at the French port of Cherbourg. They would carry passengers and mail to the liners, which, being too large to enter Cherbourg’s harbour itself, would be moored a couple of miles off shore.

At the time of the great liners’ construction, approximately 15,000 people worked at Harland and Wolff’s Belfast yard. They worked a forty-nine hour week, with only half an hour for lunch, receiving about £2 per week. They only had one week’s holiday in the summer, plus two days at Christmas, and two at Easter. Despite the tough working conditions, there were only eight fatalities reported during the Titanic’s construction, five of which were actually on the Titanic . The photograph, above left, shows the main drawing office, where rows of draughtsmen sit, producing working drawings and plans for the shipyard to use. A scale builders model of an Olympic-class liner is visible at the very rear of the room.