Work began on the third and final Olympic-class liner, Britannic, on the 30th November, 1911, on the same slipway that Olympic had vacated on the 20th October, 1910, just over one year earlier.

But in April, 1912, work on the construction of yard No. 433 came to a dramatic halt: the sinking of Titanic caused the builders, Harland and Wolff, together with the owners, White Star Line, to stop all work whilst a new and much safer design was considered. In the aftermath of Titanic’s sinking, much work was carried out, not only to make the ship safer, but to reinforce the message to passengers that lessons had been learned.

The first of these was the rather obvious changing of the ship’s name. White Star had intended to name of the last of the trio of Olympic-class liners would be in keeping with the other two, so to follow Olympic and Titanic , White Star settled on the name Gigantic, creating a natural set of awe-inspiring names. But following the disaster, White Star decided to opt for a less aggresive name given the circumstances, and settled on Britannic.

Other more structural improvements included increasing the depth of the double bottom from five to six feet, the hull was given another wall to create a double skin, and there was major strengthening work carried out in several ‘weak spots’ throughout the hull. All of this extra construction made Britannic the heaviest of the Olympic-class liners, weighing in at nearly 50,000 tons.

One of the more noticable improvements was the provision of new, much larger pairs of davits, capable of holding six lifeboats each. But only five sets had been fitted by the time Britannic was requisitioned, the rest were made up of the same type of davits fitted to Titanic . Even so, she went to war with 58 lifeboats aboard, almost three times the amount Titanic had carried. These new davits were a huge improvement on the originals, and they were so constructed as to allow the lowering of a lifeboat on either side of the ship.

Finally, in early 1914, Britannic was launched, on the 26th February, and the White Star Line announced that she would begin her regular run to New York from Southampton via Cherbourg and Queenstown in the spring of 1915.

But due to the onset of the World War, Britannic’s outfitting was delayed, as the materials and the labour-force needed to finish her were now directed almost entirely towards the war effort.

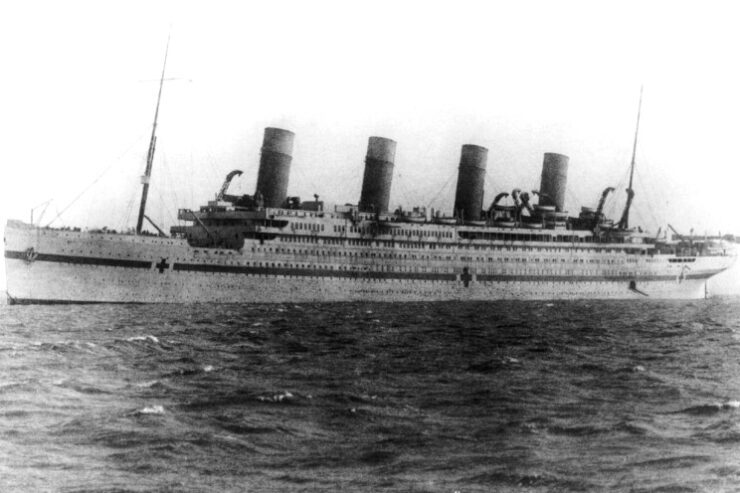

Still incomplete, and over twenty-one months since she was launched, Britannic’s fate was sealed; she was requisitioned to be a hospital ship by the Admiralty, and her interiors were hurriedly altered to accommodate the large quantity of beds, medical equipment and medical staff that would soon be filling her empty rooms.

She was painted white, complete with a broad green band along her hull, punctuated by three large red crosses, identifying her to friend and foe alike that she was a hospital ship. As an extra precaution, there were two more red crosses high up the ship on the side of the promenade deck which could be illuminated at night.

The White Star Line placed in her Captain Charles Bartlett, who had previously commanded Germanic, Cedric, and Republic II. He was nick-named ‘Iceberg Charlie’ for his seemingly uncanny ability to detect when there was a threat of ice.

By December 12th, 1915, Britannic had sailed to Liverpool, accompanied by heavily armed escorts. Ten days later, fully equipped and staffed, she departed on her maiden voyage. She sailed first to Naples to take-on coal and water, and then to her intended destination, Mudros, on the Greek island of Lemnos, where she was loaded with casualties of the fierce fighting taking place in the Dardenelles. She then returned to Southampton, arriving on January 9th, 1916.

Eleven days later, on 20th January, 1916, Britannic sailed to Naples to take on coal and water, but whilst there, she was instructed to take casualties from other smaller hospital ships. Again she returned to Southampton, arriving on the 9th February, 1916, and once the patients aboard her had all been off-loaded, she was again prepared for another voyage, this time to Augusta.

She departed Southampton on March 20th, 1916, and upon arrival at Augusta, she was again utilised to ‘free-up’ smaller hospital ships by transferring their patients to Britannic. This complete, she again sailed for Southampton, arriving back home on the 4th April, 1916.

There now came a rather peculiar period in Britannic’s short life, due mainly to the failure of the Gallipoli campaign that had been providing Britannic with the constant supply of wounded soldiers. As the campaign was effectively ended, Britannic, together with the two Cunarders Mauretania and Aquitania, was released from war service by the Admiralty on 6th June 1916. She was returned to Harland and Wolff’s yard at Belfast to continue the work needed to finish her off, ready for her regular transatlantic service.

But fate stepped-in again, as it does quite often with the Olympic-class liners, and due to new campaigns in the north of the Balkans, Mudros again became a focal point for injured troops, and soon the town’s hospitals were overrun. Just over two months since being released, Britannic was again requisitioned, along with Aquitania.

After sailing to Southampton, she was ready to depart by 9th of September, again to Naples and Mudros, but this time via Cowes on the Isle of Wight, returning to Southampton on 11th October, 1916.

A mere nine days later, she was again ready for her familiar sortie to the Mediterranean, although this time, she would take with her nearly 500 extra medical staff, accompanied by tons of medical equipment for use in Egypt, Malta and India. She was back in Southampton, which must have begun to feel like the ship’s home port by this time, on Monday, 6th November, 1916.

By Sunday, Britannic was again all set for a routine round trip, and she left Southampton, bound yet again for Naples. She arrived in Italy five days after departure, and was supposed to spend a day there coaling, but inclement weather meant she was delayed by a day. So, on Tuesday, November 21st, 1916, Britannic left the familiar port of Naples, bound again for Mudros. At about 8.00am, whilst sailing through the narrow Kea Channel, there was a huge explosion on the starboard side of the bow.

It’s still debated to this day whether or not Britannic was struck by a torpedo, or whether she ran into a mine, but whatever she did hit, the effects were almost immediate. Britannic began to slowly sink by the bow. Two lifeboats were lowered whilst the ship was still moving forward at speed, with the result that when they hit the water, the suction of the hull drew them into the stern of the ship, and the two boats, together with the people in them, were sucked into the churning propellers, killing all aboard instantly.

Captain Bartlett decided the best course of action was to make an attempt to beach her on Kea Island, some two miles away, but this seemed to accelerate the rate of sinking, so he ordered the engines to be stopped.

The fact that Britannic was only carrying about a third of her usual quota of passengers kept the death rate very low indeed, and apart from thirty fatalities caused when the two lifeboats were crushed by the propellers, everybody else aboard the stricken liner managed to escape in a lifeboat.

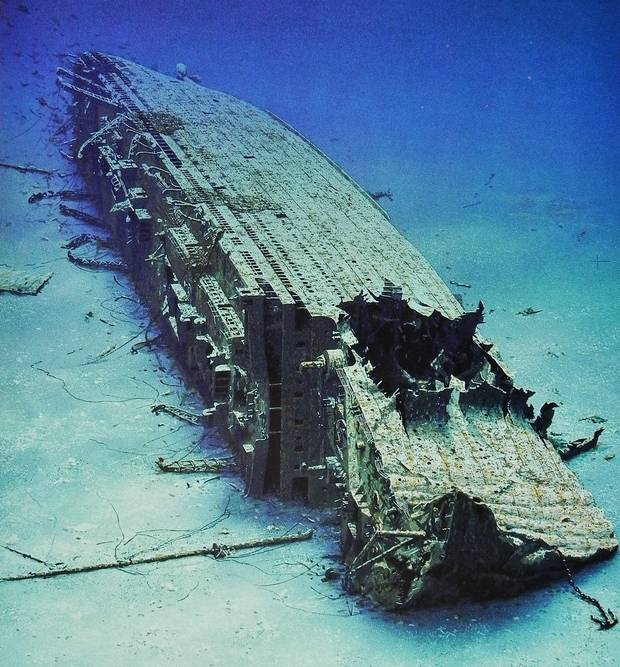

The vessel had been sinking deeper into the Aegean Sea whilst the evacuation was under way, and the last person to leave her decks was Captain Bartlett. He jumped into the sea, and swam to empty collapsible lifeboat, from where he watched the pitiful death throes of his beloved ship.

Britannic lies in nearly 400 feet of water, relatively shallow when you think of how far Titanic sank, which was about two-and-a-half miles. Britannic’s bow was actually on the sea floor while the stern was still afloat, so shallow is the ocean where she sank! She was discovered by the renowned underwater explorer Jacques Coustea on the 3rd December, 1975, largely intact, and lying on her side.