Titanic, according to the many legends, was ‘practically unsinkable’, but in reality, no ship can ever be made trulyunsinkable, even almost a century after Titanic’s conception. However, steps had been taken by the ship’s builders, Harland And Wolff, during the design of the Olympic-class liners to ensure that these vessels would be the safest ships to ever take to the seas at that time, and the key to this improvement in safety was the way the hull was sub-divided, or split-up, into watertight compartments.

Fifteen transverse bulkheads created sixteen compartments or cells, each of which could be isolated from the adjoining compartment using special doors which could be closed in the event of an emergency. However, these compartments were actually far from being truly ‘watertight’ in the way that the name suggests, and this was cruelly proven on the night of April 14th, 1912.

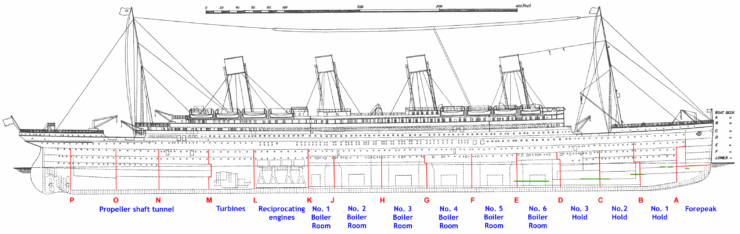

The compartments were labeled from ‘A’ in the bow to ‘P’ in the stern, and all of them came at least as far as ‘E’ deck. Additionally, bulkheads ‘A’, ‘B’, ‘K’, ‘L’, ‘M’, ‘N’, ‘O’ & ‘P’ extended to ‘D’ deck, all of them easily exceeding the Board of Trade’s requirements.

For a watertight compartment to be truly watertight, it must be enclosed on all six sides to form a box or cube within the hull. However, on passenger liners in particular, this was of course generally found to be totally unacceptable. Passengers and crew alike needed to access all parts of the ship without hindrance, and large public rooms also used up a lot of the space within the hull. It simply wasn’t practical to expect passengers to go up a staircase to get over a bulkhead, so doors were put into the bulkheads to allow access, immediately removing the ability for a flooded compartment to be kept isolated from the next.

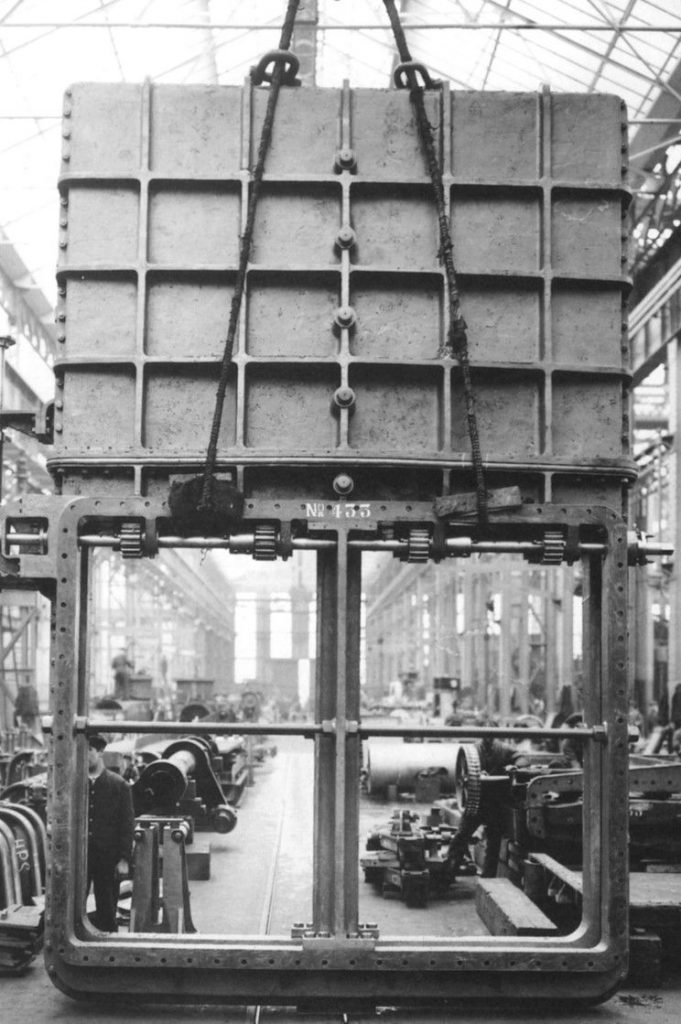

Whilst this arrangement was accepted higher-up the vessel, where the danger of flooding was relatively low, below the waterline it was of course a different matter entirely. Bulkheads ‘D’ to ‘O’, which were part of the boiler and engine rooms, were all equipped with hydraulically-operated vertically-sliding watertight doors built to Harland And Wolff’s own design. These doors could be lowered into place by a number of different methods, closing-off one compartment from the other in order to maintain the integrity of that compartment in the event of a hull breach.

Methods of closing watertight doors:

1. The doors were held in the open position by a friction clutch, and this clutch could be released by means of a control panel on the bridge or wheelhouse area. Once activated, the door could not be opened again locally, only remotely from the afore-mentioned control panel.

2. Each door could be closed at its location by flicking a switch or lever.

3. A float fitted to the door mechanism automatically activated the door if any water that might enter the hull rose to a certain level.

In the event of activation of the watertight doors, alarm bells would sound for a few seconds to warn any crew members working in the location, and allow them to escape up to the decks above using steel ladders provided for such an emergency.