It took an incredibly short period of time, a mere six months, from the meeting in London between Bruce Ismay and Lord Pirrie to discuss the new Olympic-class liners, and the actual keel-laying in December 1907 of the first of the trio, Olympic, yard No. 400.

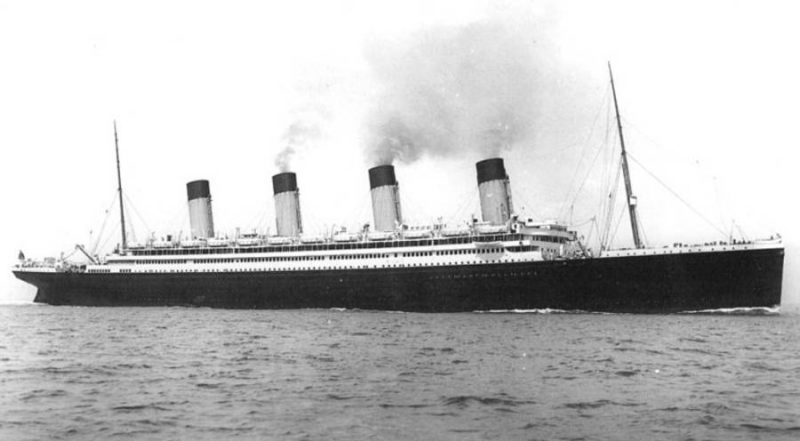

On October 20th, 1910, Olympic was launched at Harland and Wolff’sBelfast yard, and she immediately entered the record books as the heaviest man-made object at that time, although Titanic would take that crown when she was launched. Olympic was painted white for the occasion, allowing photographers to get the best images possible of this momentous event.

Olympic’s first four trips across the Atlantic were trouble-free, but on September 20th, 1911, at the beginning of Olympic’s fifth voyage to New York, and with Titanic’s future master, E.J. Smith in command, Olympic was in collision with a Royal Navy

cruiser, H.M.S. Hawke. Although nobody was injured, and both ships stayed afloat, the damage to Olympic was so severe that it took workers two weeks just to patch the damaged hull enough to allow the liner to return to Belfast, as Harland and Wolff’s were the only yard with a dry-dock large enough to repair Olympic in. Once Olympic had crossed the Irish Sea, and been dry-docked, the work to repair her took six weeks.

In the February of 1912, Olympic was again back at Harland and Wolff’s in Belfast, this time to replace a propeller after dropping a blade on another Atlantic crossing.

After the sinking of her sister Titanic in April, 1912, the White Star Line, desperate to be seen to be doing the ‘right thing’, returned Olympic to Harland and Wolff’s Belfast yard to undergo several modifications. The most visible of these was the provision of more lifeboats – the Government had been quick to change the law, and there now had to be provision for everybody on board. Another improvement was increasing the height of the forward bulkheads to the shelter deck, and the hull was given another layer of steel, creating a double-bottom.

As World War One broke out, Olympic carried on as normal, but as the war went on, the amount of passengers crossing the Atlantic dropped off quite considerably, no doubt worried about what could happen to a large ship on the open sea, and the White Star Line decided at the end of October 1914 to return Olympic to her place of birth, Belfast.

On her return journey, she came to the rescue of H.M.S. Audacious, a British battleship that was mortally wounded after hitting a mine. All of the battleship’s crew were saved, and an attempt was made to tow the ship to England, but heavy seas caused the line between the two vessels to part, and later, the battleship’s magazine exploded, sending her to the bottom.

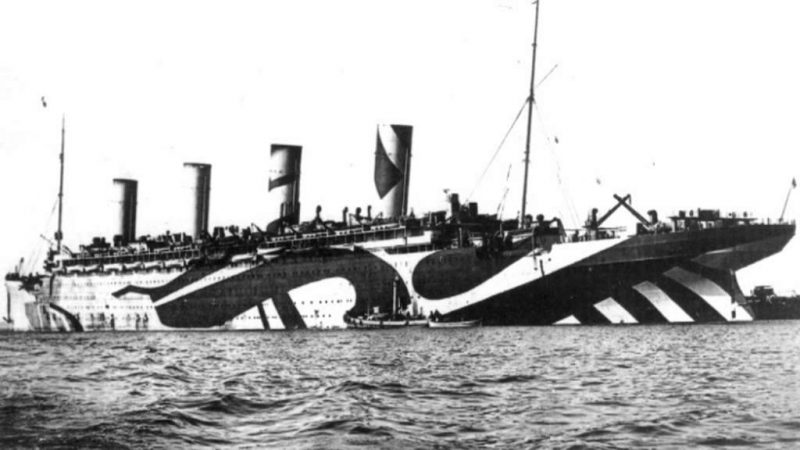

After Olympic had debarked her passengers, together with the crew of H.M.S. Audacious, White Star Line intended to lay her up in Belfast until the war was over, but in the middle of 1915, the Admiralty commissioned her to be used as a fast troop transport. She was stripped of all her luxurious fittings, and painted in her famous ‘dazzle paint’, as seen here in the photographs on the left. ‘Dazzle paint’ incorporated painting vivid shapes and patterns over every inch of the ship, which made it harder for enemy range-finders to get an accurate fix on Olympic. She could carry up to 7,000 troops at any one time.

Now assigned the suffix ‘H.M.T’, for ‘His Majesty’s Transport’, H.M.T. Olympic, under the command of Captain Bertram Hayes, sailed on the 24th of September for Mudros, Greece. Yet again, Olympic came to the rescue of a ship in trouble after being struck by a German torpedo, the French vessel Provincia.

In 1917, Olympic again returned to Belfast to have anti-submarine guns fitted, and these would be put to good use on the night of May 18th, 1918. During her 22nd troop carrying voyage, the crew of Olympic spotted a U-boat, U-103. The Captain ordered the ship turned in order to ram the submarine, and as Olympic approached the seemingly unaware sub, she opened fire with her anti-submarine guns, finally alerting the submarine’s crew of her presence.

But it was far too late, and Olympic tore through the hull of submarine, sending it to the bottom. Some of the sub’s crew were rescued by an American destroyer that was on hand. This remarkable feat of bravery was the only recorded instance of a merchant vessel sinking any type of warship during World War One, and the American soldiers aboard her organised a collection in order to have a commemorative plaque placed in one of Olympic’s lounges to remind future travelers of her proud war-time service.

Olympic continued to cross the Atlantic on a regular basis, and did so until the end of November, 1918, when she was commissioned to carry Canadian troops back home by the Canadian Government. She did this for the next nine months, and eventually returned to Harland and Wolff’s Belfast yard, this time to be refitted and returned to her regular passenger-carrying service.

During her refit, workers investigating a leak in her hull unbelievably found a dent caused by a torpedo that had failed to detonate! During her $2.5 million refit, Harland and Wolff converted her to burn oil, which was easier to load, and a lot more efficient than coal, and it also meant she required about 300 less crew, making huge savings for the White Star Line. ‘Old Reliable’ returned to traffic, and continued where she had left off, a successful and much adored ship, loved by many.

By 1933, transatlantic passenger numbers had dwindled, mainly due to the crash of 1929, and the White Star Line was merged with Cunard, and became the Cunard White Star Line. The newly merged company began to sell off some of its ships, and Olympic’s future was put in doubt due to her age, as she was about 25 years old at this time.

Olympic’s good fortune throughout the war, together with her reliability in normal service, came to an abrupt end soon after this merger. In dense fog, approaching New York, she ran down and sank the Nantucket Lightship, killing seven of the lightship’s eleven crew. Olympic, and her owners, Cunard White Star, were found to be responsible for the disaster, and had to pay $500,000 in compensation.

By the time 1935 arrived, time was up. Olympic was retired, and for the only vessel of the trio of Olympic-class ships that actually managed to perform her assigned duty – to carry passengers across the Atlantic to New York – the future looked very bleak. Cunard tried to find a buyer for the still popular Olympic, but nobody wanted her. She was sold for scrap, and she sailed, under her own steam, for Jarrow on the River Tyne in the North East of England on October 11th, 1935.

For two years the vessel was stripped of her luxurious fittings, her varnished paneling, and her superstructure, leaving just the massive hull, pictured here on the left, which in 1937 was towed to Inverkeithing in Scotland for the final part of her disposal.