- Age: 39

- Date of Birth (D.O.B.): 7th February, 1873

- Place of Residence: Belfast, Ireland

- Embarked at: Belfast, Ireland (Harland and Wolff Guarantee Group)

- Ticket Number: 112050

- Price Of Ticket:

- Cabin Number: A-36

- Class: First Class Passengers

- Destination: New York City, New York

- Survived: No

- Died: 15th April, 1912 at sea

Thomas Andrews boarded the Titanic at Belfast, Ireland, traveling to New York City, New York.

Thomas Andrews was part of the nine-man Titanic Guarantee Group, which also included Henry William Marsh Parr, William Campbell, Roderick Chisholm, Alfred Fleming Cunningham, Anthony Wood Frost, Robert Knight, Francis Parkes and Ennis Hastings Watson.

Thomas Andrews was lost in the sinking of the Titanic, as were all the members of the Titanic Guarantee Group, and his body was not recovered or identified.

Thomas Andrews was born at the Andrews family home, Ardara, in Comber, on 7th February, 1873. His father, the Right Honourable Thomas Andrews Sr., was a distinguished local politician, whilst his mother, Eliza, was Lord William Pirrie’s sister. Lord Pirrie of course, was the owner of Harland and Wolff, so that meant that Thomas Andrews was Pirrie’s nephew. Other influential family members included his uncle, who was a High Court judge, and his brother John who would go on to become Northern Ireland’s Prime Minister, no less.

In 1884, Thomas Andrews, like his father before him, was entered into the Royal Belfast Academical Institution at the seemingly-tender age of 11, but left in 1889 when he was 16 to begin working for Harland and Wolff as a premium apprentice.

This meant that his parents would have paid Harland and Wolff anything up to £100 when he started his apprenticeship, and in return, Thomas Andrews would be guaranteed a position at the shipyard at the end of his apprenticeship. Despite the fact that the owner of the shipyard, Lord Pirrie, was Thomas Andrews’ uncle, he certainly didn’t seem to enjoy any favouritism; Thomas Andrews worked hard during his apprenticeship, and in time, this would be duly recognised by the shipbuilders in the near-future.

But for now, he had to buckle-down, and he volunteered for many after-hours ‘self-improvement’ classes to learn different trades, therefore broadening his horizons in marine engineering, and at the same time showing his employers how keen he was in shipbuilding in general.

Thomas Andrews was made manager of the construction works at Harland and Wolff in 1901, and in the same year he was also made a member of the highly-esteemed Institution of Naval Architects, not bad going for a 28 year-old. Around this time Thomas Andrews was heavily-involved with the construction with the White Star Line’s ‘Big Four’, the quartet of Celtic, Cedric, Baltic and Adriatic.

In 1907, Harland and Wolff rewarded Thomas Andrews’ hard work and sheer enthusiasm for shipbuilding by making him Managing Director, which, it must be stated, had nothing to do with his uncle owning Harland and Wolff, it was hard-earned on Thomas Andrews’ part, and it couldn’t have happened to a nicer man.

Thomas Andrews was almost universally adored by the workforce in the Belfast shipyard, and he inspired them with his warmth and humility. He had the total respect of his colleagues, and led by example, creating trust among the workers.

The year 1907 was also the year the biggest project Harland and Wolff had ever undertaken began – the construction of the Olympic-class liners. The keel of the first of the trio of superliners, Olympic, was laid in December of that year.

On June 24th, 1908, Thomas Andrews married Helen Reilly Barbour, whose father was previously on the board of directors of Harland and Wolff. They lived close to Harland and Wolff at ‘Dunallon’, in Belfast. Two years later, Helen bore a child, Elizabeth Law Barbour Andrews, whom Thomas nicknamed ‘ELBA’, due to her initials! Weeks before the birth, Thomas Andrews had taken Helen to the shipyard at night to show her Titanic under construction, and also to view Halley’s Comet, which was visible at this time too.

(How terribly-ironic… Halley’s Comet was just a tiny bright speck in the far distance, just like Titanic after the collision. Even more ironic… Halley’s Comet returned in 1986, the year after Robert Ballard found the wreck of Titanic.)

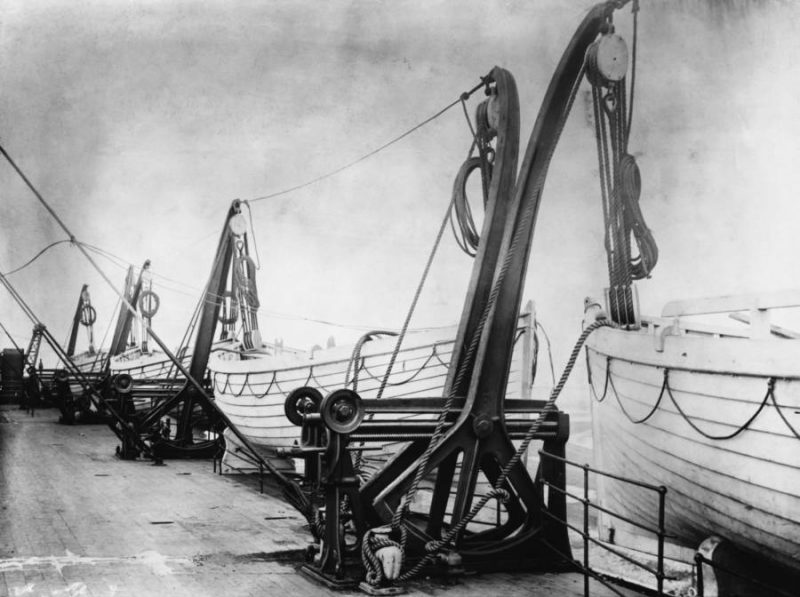

Thomas Andrews also headed Harland and Wolff’s guarantee Group, an elite collection of nine of the best men in their field who would be aboard a vessel on its maiden voyage to see that all went well, and if a problem did show up, their collective skills would hopefully see the problem overcome or temporarily-eased. Thomas Andrews had previously travelled on 3 other ships maiden voyages, the last of the Big Four, Adriatic II , in 1907, Oceanic II, and of course, Olympic. Now, as 1912 loomed, he would be making the trip to New York again, aboard the largest vessel in the world… Titanic.

Titanic’s sea trials, which had been scheduled for April 1st, 1912, were postponed due to high winds, so they were rescheduled for the next day, the 2nd April. Thomas Andrews was aboard of course, and at the end of day, when Titanic returned to Belfast to drop-off all of the people not traveling to Southampton, Thomas Andrews stayed aboard for the journey to Southampton. It would be the last time Thomas Andrews would set his eyes on Belfast.

When Titanic arrived in Southampton after its near-600 mile journey from Belfast, there was little under a week to prepare Titanic for its departure day, and as well as stocking the ship with provisions and cargo, there was much, much work to be done by the crew, particularly regarding familiarisation with the new systems on the huge ship. Thomas Andrews would have acted as a ‘consultant’, briefing heads of departments, showing crew members how various things operated, and also troubleshooting any problems that might arise during the lead-up to the April 10th departure.

During Titanic’s maiden voyage, Thomas Andrews the perfectionist was never far from his work, and he almost-continually carried a small notebook around the ship in which he would jot down problems or refinements that he thought should be carried out to Titanic, or perhaps the next ship in the trio of Olympic-class liners, Gigantic. Several modifications had been made to Titanic this way, after experience gained with Olympic, the most obvious of which was the alterations to the windows on the forward part of the promenade deck.

Another alteration, carried-out at the same time as the promenade deck windows, was the addition of another First Class cabin, A-36, which doesn’t actually appear on any deck plans. This was Thomas Andrews’ cabin for the maiden voyage, and at the very moment of the collision, he was in his cabin studying the ship’s plans, no doubt planning future refinements.

So engrossed was Thomas Andrews in his work, that he, like many others, didn’t feel the impact, and it was only when Captain Smith sent for him that he was alerted to the fact that something was amiss. Andrews conducted a rapid tour of the ship to assess the extent of the damage, but he must have known long before he returned to the bridge to report to Smith that Titanic’s fate was already sealed.

Thomas Andrews was seen trying to convince reluctant passengers to enter the lifeboats during Titanic’s sinking, and it worked too – if Thomas Andrews ordered you into a lifeboat, then surely it was for a very good reason.

As for Thomas Andrews himself, he seemed to have no thoughts whatsoever of self-preservation, instead preferring to ensure the safety, indeed the very survival of other passengers. Around 2.10a.m., a steward making his way upto the boat deck, John Stewart, saw Thomas Andrews staring at Norman Wilkinson’s painting ‘The Approach To Plymouth Harbour’, which hung proudly above the mantlepiece in the First Class Smoking Room.

Stewart asked, “Aren’t you even going to try for it Mr. Andrews?”

Thomas Andrews never replied, and his eyes remained fixed on the painting, his redundant lifejacket lay nearby on a table.

No one would ever see Thomas Andrews again, his body was never recovered, and the world had lost a true gentlemen.

To the people of Comber, his colleagues at Harland and Wolff, and of course his family, the confirmation of his death came as a huge shock, and in a very short space of time, it was decided to create a memorial to this great man who had, and continued to inspire so many.