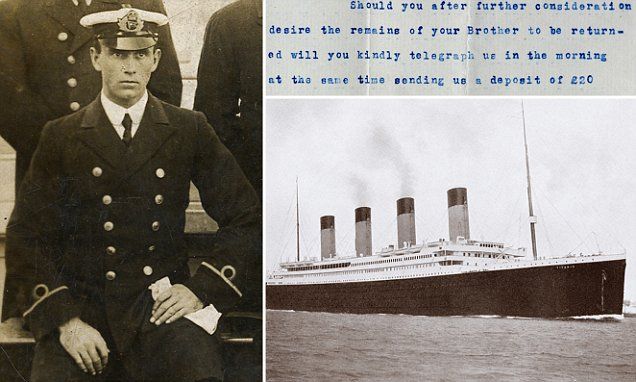

James Paul Moody was born in Scarborough, England on the 21st August 1887. His family were not a seafaring family, far from it, but the pull of the sea must have been fairly strong, because at the age of 14, Moody went to sea to serve his apprenticeship under sail.

In 1911, at the age of 23, he joined the White Star Line and was assigned to the giddy splendour of Oceanic II, a far cry from the sailing vessels he had been posted aboard during his apprenticeship, and crossing the North Atlantic in her elegant comfort must have made the notorious North Atlantic seem like a millpond compared to crossing in the wooden-hulled sailing ships that he’d been used to.

Among Oceanic II’s officers at that time were Charles Lightoller and David Blair, and together with James Moody, the three men would all soon be receiving telegrams from the White Star Line informing them of their new posting, aboard the largest liner in the world – Titanic. Again, Moody would be moving onto an even bigger, even better vessel, impossible as that seemed after his short period of time aboard Oceanic II!

James Moody received a telegram from the White Star Line informing him to report to the company’s Liverpool offices on the morning of March 26rd, 1912, from where he would travel to Harland & Wolff’s yard at Belfast, where Titanic was in the last stages of her fitting-out. The day of her sea trials, April 1st, was also fast approaching. Accompanying Moody on the trip to Belfast were Titanic’s other three junior officers, Herbert Pitman, Joseph Groves Boxhall and Harold Godfrey Lowe.

He arrived in Belfast the next morning, and boarded Titanic, signing the particulars, or log, and presented himself for duty to Chief Officer William McMaster Murdoch* at Midday.

Sailing Day

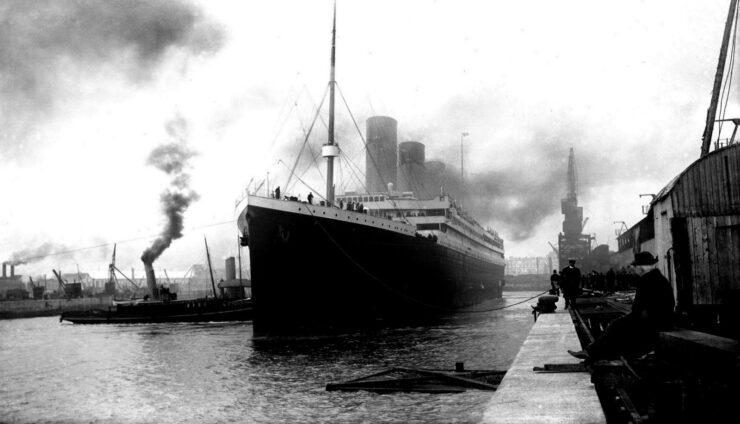

In Southampton on the morning of Wednesday 10th April 1912, Titanic’s sailing day, Fifth Officer Lowe and Sixth Officer Moody supervised, amongst many other things, the lowering of two of the starboard lifeboats for the benefit of the Board Of Trade’s Captain Maurice Clarke, who was aboard to ensure that the vessel met the standards laid down in the Merchant Shipping Acts.

As noon approached, and Titanic’s departure was imminent, Moody was stationed at the gangway, and unbeknown to him, or anyone else at the time, he unwittingly saved the lives of half-a-dozen crewmen. The men concerned had been drinking in the public houses of Southampton, but had been delayed, and as they dashed down the dock side, they saw to their horror that the gangway had been detached from Titanic, and they could not get aboard the departing liner. Moody decided to call on the spare crew who were always aboard at departure time in case of just such an emergency, and the six men, brothers Bert, Tom and Alf Slade, together with two stokers and a trimmer, all lived to tell the tale of how they came within 10 seconds of probably being lost on the Titanic, thanks to the actions of Sixth Officer Moody.

April 14th/15th, 1912

On the night of April 14th, Moody was on duty on the bridge, together with First Officer William McMaster Murdoch. At just before 11.40p.m., the chilling sound of the Lookout’ bell being rung three times could be heard on the bridge, and only a second or two later, the telephone on the bridge started to ring. Moody was by now an experienced seaman, and he knew instinctively that the three bells meant danger, and when he answered the telephone, he didn’t bother exchanging pleasantries with Frederick Fleet, the lookout who had first spotted the iceberg.

“What do you see?” asked Moody.

“Iceberg right ahead!” answered Fleet in the crows nest.

“Thank you” said Moody, and replaced the telephone, and almost at the same time, he repeated Fleet’s warning to First Officer Murdoch.

Not long before 1.30p.m., Fifth Officer Lowe and Sixth Officer Moody had a quick conversation, the eventual outcome of which was the difference between life and death. Lowe pointed-out to Moody that he’d sent a handful of lifeboats away into the night without a single officer aboard them, and suggested that it would be advisable to have an officer in the next boat they loaded, No. 14. Moody sealed his own fate when he heroically told Lowe to board the lifeboat, and that he would find one later. Traditionally, the younger officer would’ve been given the place in the lifeboat, giving the younger men a chance to survive, whilst the older, more experienced officer would be absorbed in the evacuation of the sinking vessel.

Moody declined the offer, and died.

* Remember, the officer reshuffle hadn’t taken place yet, so at this point in time, William McMaster Murdoch was the Chief Officer, and would be until close to Titanic’s departure day.