The Norse word ‘iceberg’ translates, not surprisingly, into ‘mountain of ice’. The mountain of ice that Titanic tragically encountered in April, 1912 was first formed over 5,000 years ago, when layer after layer of snow and ice were compressed and crushed by yet more falling snow to form part of the immense Greenland Glacier.

These glaciers are constantly moving, sometimes as much as 65 feet per day, due to the immense weight of the Greenland Ice Cap pushing down on them. As the glaciers reach the sea, large chunks break-off into the Baffin or the Labrador Sea, and eventually get caught-up in the colds of the Labrador Current, which takes them into the open waters of the North Atlantic. But once they meet up with the warm waters of the Gulf Stream, most icebergs melt quickly, although in 1926, an iceberg drifted to within 150 nautical miles of Bermuda. Between 10,000 and 15,000 icebergs break-off every year, but only about 500 of these actually make it as far south as the North Atlantic shipping lanes.

As much as 85% of an iceberg’s bulk is underwater, and because of the strong currents that can push on the underside of it, it’s not uncommon to see an iceberg moving against a strong wind. ‘Bergs are composed almost entirely of fresh water, and as the iceberg melts, its centre of gravity can change, causing it to roll over to a new position. The part of the newly exposed surface appears darker than the rest of the ice, and are known as ‘blue bergs’. It’s believed that the iceberg Titanic struck was a blue berg, making it very difficult to spot at night.

Icebergs were not a new hazard to shipping in the North Atlantic when Titanic sank. Records show that as far back as 1833, the Lady Of The Lake sank with the loss of 70 souls after colliding with an iceberg in the Grand Banks area. Between 1882 and 1890, 14 vessels were lost and 40 seriously damaged due to ice in this notorious part of the hostile North Atlantic, and this figure doesn’t even take in the huge amount of fishing vessels operating in that same period.

The iceberg that Titanic collided with on that bitterly-cold April night in 1912 was reported in the newspapers as being anywhere between 50-100 feet high, and anything between 200-400 feet in length. Although only a handful of people aboard Titanic saw the actual iceberg, no-one managed to get a photograph of it, due to the fact that it all happened so quickly, and as it was night-time, everybody was below-decks.

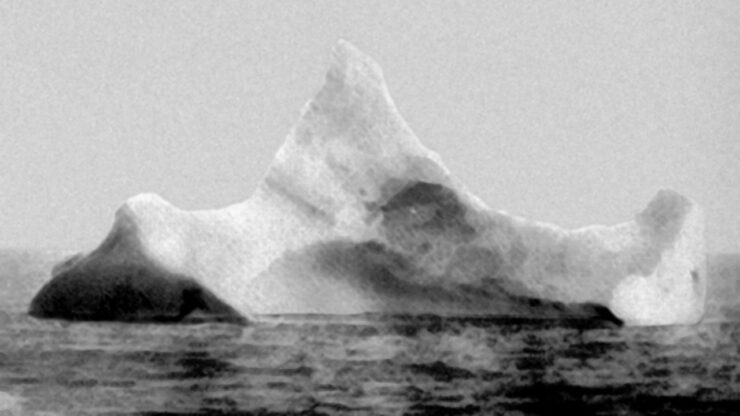

The two people with perhaps the best view were undoubtedly the Lookout, Frederick Fleet and Reginald Lee. Fleet drew this picture of the collision shown here on the left, although the size of the iceberg has been greatly exaggerated. But in the days after the sinking, various people took pictures of icebergs in the area where Titanic sank, and who knows, one of them could well be the very one that sank her.

The first of these photographs is seen here on the left, and was taken by Captain de Carteret of the Minia, one of the vessels hired by the White Star Line to search for bodies following the sinking. The second photograph, which is pictured here below right, was taken by the chief steward of the liner Prinze Adelbert, which was passing through the area of the sinking on the morning of Monday 15th April. Although the steward hadn’t yet heard about the sinking, he saw that there was a line of red paint along the base of the iceberg, a sure sign that it had probably been in contact with the hull of a vessel, though we will never know whether or not that vessel was Titanic .

In the weeks following the sinking, the US Navy despatched two cruisers to patrol the Grand Banks area, the Birmingham and the Chester, whose job it was to report the location of icebergs to the vessels using the North Atlantic shipping lanes. Icebergs were tracked as they entered the hazardous areas, and there was wider reporting of ice by all shipping at this time too.

In November 1913, the first International Conference of S.O.L.A.S. (Safety of Life at Sea) took place between maritime representatives of countries from all over the world. The formation of a seasonal ice patrol was discussed, and as a result of these discussions, in February 1914, the President of the USA gave the go-ahead for the formation of the Ice Patrol Service, who as well as the reporting and tracking services, would also undertake research into icebergs, and their behaviour.

Today, the Ice Patrol Service still exists, although the equipment they use is state-of-the-art technology. Drift buoys are parachuted into the sea from the Ice Patrol Service’s C-130 aircraft. These buoys send back information via satellite such as the water temperature and current direction, which scientists can then use to determine where the icebergs are most likely to appear, and how quickly they are likely to deteriorate.

Every year, on the anniversary of the sinking, a C-130 aircraft flies over the location where Titanic foundered, and drops a wreath to remember and pay tribute to the people lost on that April night.