Titanic’s popular and well-respected bandleader, Wallace Hartley, was no stranger to the oceans, or the big liners that crossed them, having previously been the bandleader on the rival Cunard line’s quadruple-funneled sister ships Lusitania and Mauretania, but the lure of playing on the biggest and most decadent ship in the world, and playing to the richest and most distinguished passengers on the North Atlantic run all helped to convince him that the change would be for the good, plus there was a pay rise to consider too.

Wallace Hartley, together with the rest of the band members, were traveling as Second Class passengers, and were not actually on the White Star Line’s payroll. Their employers were Messrs. C.W. & F.N. Black of Liverpool, and they paid their wages just like any other agency, after the White Star Linehad paid the agents. However, unlike any other agency, the food and lodgings for Wallace Hartley’s ‘gig’ were outstanding, and Hartley ate in the modest, though still beautiful surroundings of the Second Class Dining Room, together with the rest of the band members.

Although often referred to as ‘The Band’ or ‘The Orchestra’, in truth there were actually two entirely seperate units, that performed music at different times, and in different places. Wallace Hartley’s quintet played at teatime, after dinner concerts, Sunday service etc. Then there was a trio of violin, cello and piano that played in the reception room outside the A la Carte Restaurant and the Cafe Parisien.

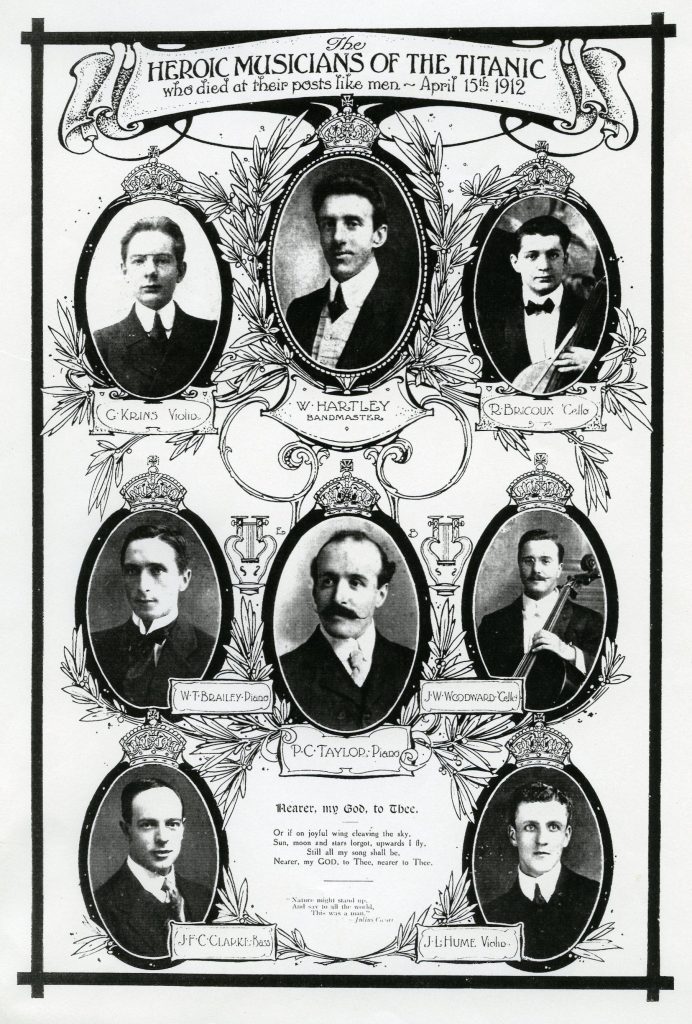

These separate units usually worked independently of each other, and it is pretty certain that when Hartley assembled the band on the night of the sinking, it was the first time the eight of them would have all played together. The additional trio were predominantly aboard Titanic to add to the Cafe Parisien’s continental flavour, and this was reinforced by the cosmopolitan inclusion of a French cellist, Roger Marie Bricoux, and a Belgian violinist, Georges Alexandre Krins.

The names of Theodore Ronald Brailey, Bricoux, John Frederick Preston Clarke, Hartley, John Law Hume, Georges Alexandre Krins, Percy Cornelius Taylor and John Wesley Woodward were permanently inscribed into the history books on the night of April 14th, 1912, and their totally unselfish deeds during that night serve as a constant reminder of the devotion to duty many people displayed during the sinking.

Shortly after midnight, as the lifeboats had begun to be loaded, Hartley assembled his band in the First Class Lounge, where many of the First Class passengers were now assembling, and began to play. Many people later commented on how strange it seemed to be wearing a lifejacket, awaiting orders to get into the lifeboats, whilst the band continued to play away as though nothing had happened. Later, as more and more people began to realise the seriousness of the situation, and began to file onto the Boat Deck, so too did Hartley, reassembling his band on the Boat Deck close to the entrance of the Grand Staircase.

What went through their minds as they played together on that night can only be guessed. As the slant of the decks increased more and more, did they even consider that this was their last hour alive, or did one or two of them hold out a slight hope that eventually, one of the officers would amble over, and instruct them into a lifeboat? Whatever their thoughts were, we will never know. All eight bandsmen were lost.

What the band played as Titanic slowly began to sink is never disputed – ragtime, waltzes, specific tunes noted by survivors included ‘Alexander’s Ragtime Band’ and ‘In The Shadows’. But a question mark still hangs over what the last song was as Titanic’s stern began to rise clear of the Atlantic Ocean, and indeed, would it be physically possible for them to play anything in those conditions?

The sensible money is of course on ‘Nearer, My God, To Thee’ – no sooner had Carpathia docked in New York, than the papers were reporting Wallace Hartley and the others in the band playing it to the end, although it must be pointed out that these same newspapers had reported that Titanic was under tow and heading for Halifax! But many other reliable witnesses remember ‘Song d’Automne’. We will never really know of course, but as none of the band survived, then the only truly reliable witnesses were tragically lost at 2.20am, 15th April 1912. But that, in my mind, is trivial. The fact that they did play, in those terrible circumstances, and faced with almost certain death, is enough.

Almost two weeks after the disaster, Wallace Hartley’s body was recovered from the icy Atlantic, still wearing his bandsman’s uniform, and with his music box still strapped to his body. His body arrived back in England at Liverpool on the 12th May, aboard the White Star liner Arabic. His coffin was loaded onto a horse-drawn hearse for the 60-mile journey back to Colne.

Over 30,000 people turned out to pay their last respects to Hartley at his funeral on 18th May, and a procession to the Bethel Independent Methodist Church, where Wallace Hartley once sang in the choir, was almost half a mile long. As he was buried in the small cemetery on the edge of Colne, an orchestra played ‘Nearer, My God, To Thee’, and the music of the hymn, together with a violin, are carved into his ornate gravestone.

A fitting memorial to the eight bandsmen is a plaque at Liverpool’s Philharmonic Hall. It was unveiled on 4th November, 1912, and has stood the test of time well, as the hall was destroyed by fire in 1933. A new hall opened six years later, and somehow, the building andthe plaque within survived the heavy bombing of the Luftwaffe, despite nearby buildings being totally obliterated. (Can you spot the mistake on the plaque?)