It would seem that you can´t have a good story without a conspiracy theory raising its ugly head these days, and the story of the Titanic is no exception.

Robin Gardiner, a plasterer from Oxford, England, has written a book, ´Titanic – The Ship That Never Sank´, in which he goes to great lengths to persuade the reader that the loss of the Titanic was basically an insurance rip-off that went very tragically wrong.

Robin Gardiner’s ´Alternative Scenario´ is repeated word-for-word here, starting with Olympic´s collision with H.M.S. Hawke at Southampton.

When the helmsman of HMS Hawke, on hearing Cdr. Blunt´s order to port the helm as the cruiser and Olympic approached the Bramble Bank, turned the wheel the wrong way, swinging the warship´s armoured bow towards the liner, he set in motion a chain of events that would leave more than 1,500 dead.

With its helm jammed, the cruiser smashed into Olympic´s starboard side with such force that both ships were seriously damaged, although just how seriously nobody knew. Only after the liner could be dry-docked would the extent of her injuries become apparent.

The Royal Navy convened an inquiry within days. After hearing the evidence wholly from naval personnel the inquiry, unsurprisingly, exonerated their vessel from all blame. This must have been seen as the ´writing on the wall´ by the management of the White Star Line. They quite possibly realised then and there that their chances of collecting anything from the insurance companies was practically nonexistent, although they continued to fight the case until 1914.

As it was, it took a fortnight of emergency patching to Olympic´s hull before she was in any fit state to attempt the voyage from Southampton to Belfast for more complete repairs. Able only to use one main engine, the crippled liner made the voyage at an average speed of about 10 knots, wasting the exhaust steam from the one usable engine.

This steam would normally have driven the central turbine engine, which shows that this engine, its mountings or shafting, had been damaged in the collision. As this engine sat on the centerline of the vessel, immediately above the keel, which the damaged propeller shaft ran through, we can reasonably assume that the keel itself was damaged.

Once back at Belfast the damage could be fully assessed. A broken keel would entail expensive and extensive repairs, which would keep the ship in the yard and not earning money for months. The emergency patch had failed during the short trip back to the builders, showing that the hull was no longer structurally sound.

To make matters worse, in order to repair Olympic, labour would have to be diverted from Titanic and would delay her completion. This means that White Star Line would be even more out of pocket due to lost fares. They had lost £250,000 (£10 million at modern rates) in fares alone during the time that neither vessel had been fit for service.

Since her launch more than three months before, in response to suggestions made by J. Bruce Ismay following Olympic´s maiden voyage, alterations had been carried out to Titanic´s B and C decks. Cabins had been fitted and new portholes cut, altering her appearance slightly but not so much that she no longer looked like her sister

It was immediately obvious to the builders that it would be quicker to complete Titanic than to repair Olympic. Accordingly, the alterations to B deck were torn out and the original, much simpler, layout reinstalled. At the time, the alterations to Forecastle Deck C were overlooked in the rush and the extra portholes remained.

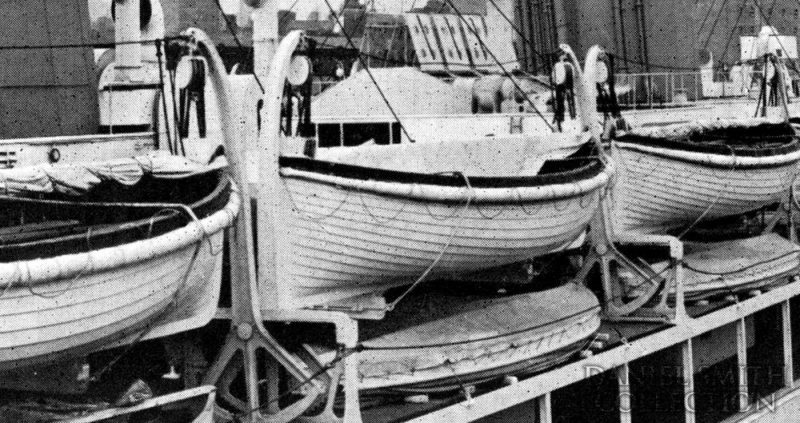

Otherwise Titanic was reconverted to Olympic specifications, at least outwardly, where necessary using parts cannibalised from her slightly older sister, such as instruments from the bridge, compass tower and lifeboats. Changing the ship´s name would have presented no difficulties for the highly skilled workforce at Harland and Wolff.

Almost two lunar months after the Hawke / Olympic collision, the reconverted Titanic, now superficially identical to her sister except for the C deck portholes, quietly left Belfast for Southampton to begin a very successful 25-year career as Olympic.

Back in the builders´ yard, work progressed steadily on the battered hull of Olympic. The decision to dispose of the damaged vessel would already have been taken. It must have been obvious from quite early on that the vessel was beyond economic repair, so these repairs need not have been quite as thorough as they otherwise might have been. Instead of replacing the damaged section of keel, longitudinal bulkheads were installed to brace it.

The torn plating and buckled ribs were straightened or replaced, a new propeller shaft and propeller was fitted and the damaged central turbine propeller shaft was patched up.

The windows on B deck were altered to resemble the layout of Titanic before re-conversion. The cabins, which should have been immediately inboard of the altered windows, were never completed and B deck remained effectively a promenade deck from which a person walking along could see the lifeboats, if they were swung out, just as Steward Alfred Crawford did on the night of the sinking.

Parts which had been cannibalised for Titanic were now replaced with the ones originally intended for that ship, as they became available. These were mainly parts such as bridge instruments, which were of a more delicate nature than the structure of the vessel and had therefore not already been fitted.

Even as this work was going on, the ship pretending to be Olympic was brought back to the builders, ostensibly to have a propeller blade replaced, but in reality to have the conversion to Olympic´s layout completed.

A propeller blade change was a one-day job to the experienced workforce at the Belfast yard but, mysteriously, the work took a week. When the ship left the yard at the end of the week, the porthole layout on the starboard side of the Forecastle Deck – Deck C – appears to have changed from the 16 portholes of Titanic to the 14 of Olympic.

Titanic´s maiden voyage had been set for 10 April 1912, so time was short. As a result, many things were skimped, among them the lifeboats, some of which leaked like sieves when used on the night of the disaster.

Trials, which for Olympic had taken two full days, took only one working day for Titanic, half of which was used up by a 4 hour cruise at moderate speed. Effectively, the ship was not tested at all. No doubt at least some of those aboard the vessel knew just how fragile the patched up hull might be.

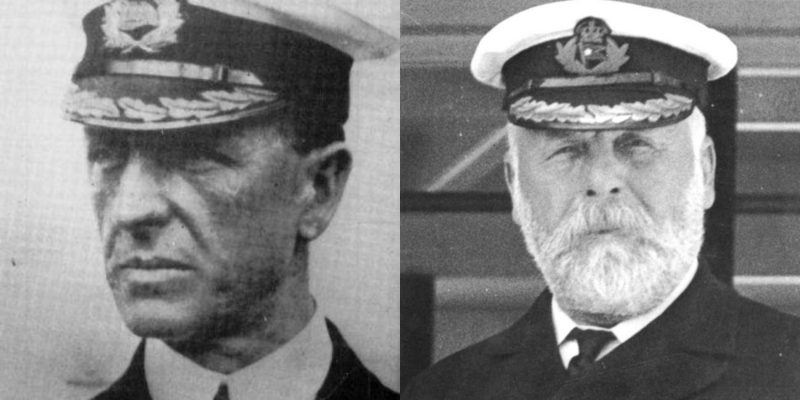

The plans to dispose of the Titanic were, by this juncture, complete. Even as she went through her pitifully inadequate trials, word was on its way to Captain Lord of the Californian to put to sea.

Californian was to proceed immediately to position 42 minutes 5 degrees N, 50 minutes 7 degrees W and there to await the arrival of the Titanic on the night of 14 / 15 April. Despite the coal shortage Californian was ready to depart on the 5th, but because of the inordinate hurry to leave port the wireless operator did not have enough time to pick up the correct charts for the North Atlantic. Captain Lord must have been instructed to await Titanic´s signals – coloured rockets – before closing and taking off her people.

Californian arrived at the rendezvous point in good time and her skipper settled down to await the liner´s appearance, or at least her rockets. His engines were standing by, as was he, there was nothing more he could do.

It is more than likely that another ship was also laid on to assist Californian in removing all the passengers and crew from Titanic. The name of this ship remains a mystery, but at least a partial description exists which gives a rough size, about 15-20,000 tons. The provision of this nameless vessel turned out to be a mistake.

Titanic left Southampton more or less on time and the voyage proceeded quite normally, at least as far as the passengers were concerned. Captain Smith headed toward his rendezvous with the Californian and whatever other vessel or vessels were waiting. This was the reason for Titanic´s late course change.

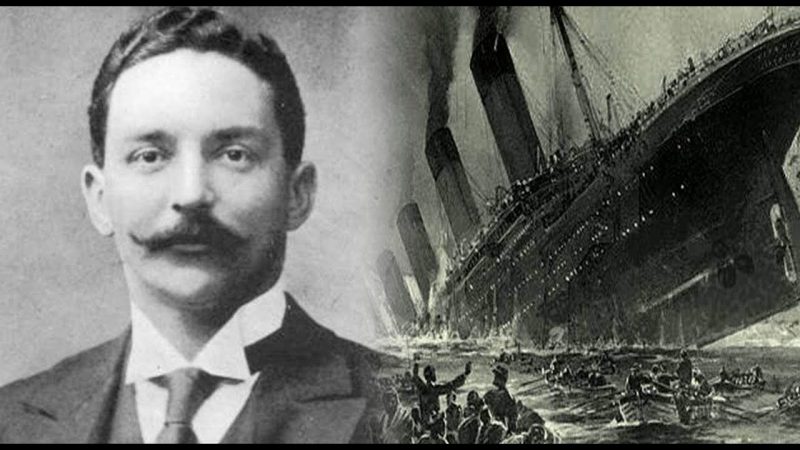

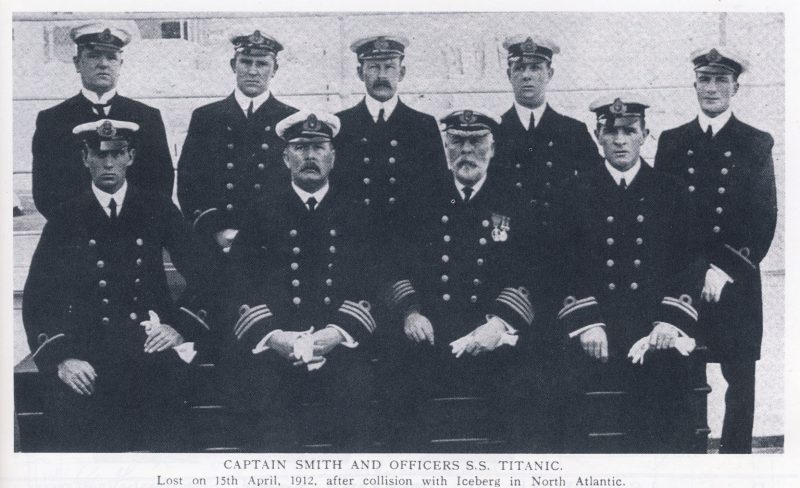

Only the senior officers knew what was planned – Captain Edward John Smith, Chief Officer Wilde, aboard specially for this reason, and First Officer Murdoch. Murdoch took up his position on the bridge of his own volition. He was not officially on duty during the time leading up to the collision but was possibly watching for the waiting rescue ships.

Although well aware of the presence of icebergs, the Titanic´s officers were confident that they would see a berg in plenty of time to avoid it, which was probably correct. What lay in Titanic´s path, however, was not an iceberg with its white fringe on top and line of phosphorescence at the waterline, but one of the rescue ships. This vessel had its lights out and had probably been damaged by the ice. For this reason Titanic´s lookouts, who were concentrating on searching the sea ahead of the ship for ice, failed to see the darkened silhouette of the blacked out ship until it was too late to avoid a collision.

Titanic crashed into the waiting vessel, tearing at least one of that ship´s lifeboats down into the sea where it remained afloat, now attached to the Titanic, probably by its own falls. The rescue ship was quite severely damaged in the collision, so badly that she took no further part in the proceedings except to confuse everybody by firing a series of white distress rockets. Titanic, still turning to port, swung away to the south and slowed down while the other vessel limped away to the north.

The initial collision between the two ships must have been nose to tail, which, of course, lessened the impact but did not prevent the mystery vessel´s steel hull from punching a hole in Titanic´s starboard bow below the waterline. This hole penetrated at least as deep as the firemen´s alleyway.

The impact and the vibration of Titanic´s engines going astern shook a mass of ice free from where it had accumulated on the rigging and wireless aerials. Then, as the other ship swung around under the impact, her hull came into contact with yet more of Titanic´s plating, starting rivets and opening seams. The damage to Titanic which breached the watertight integrity of the firemen´s passageway could not have been caused by ice without a tremendous shock being felt throughout the ship.

In the very best ´ram them, damn them´ attitude of the day, the officers commanding Titanic put as much distance as possible between themselves and what they believed at the time to be their accidental victim. Momentarily the plan to dispose of their own ship was forgotten as they moved southward, away from the waiting Californian. By the time the required pyrotechnic signals were remembered Titanic was too far from the Californian for them to be seen, but neither Captain Smith nor Captain Lord would be aware of this.

The third vessel, damaged in the collision, was still close enough to see Titanic´s powerful red, white and blue socket signals but not near enough for her own, more feeble rockets to be seen from the liner. It was these ordinary rockets that were seen from the Californian, where Captain Lord was patiently waiting for a more colourful display.

That the officers of the watch on Californian´s bridge should have roused the wireless operator is undeniable, if they thought that they were looking at distress signals, but they thought no such thing.

As well as the damaged, rocket firing vessel, yet another unidentified ship lay between Titanic and Californian, as Captain Rostron saw when it grew light the following morning. This was the ship seen from the deck of the sinking liner and seen later from the Titanic´s small boats. E.J. Smith and his senior officers, the only people aboard Titanic who knew of the arrangement with Californian, must have believed that the lights were hers.

According to the prearranged plan, Californian would close the gap between the two ships and effect a rescue. This is the only possible explanation (unless Captain Edward John Smith had lost his mind) for the go and return order which was given to some of the lifeboats.

The mystery ship had already demonstrated that she was obvious to Titanic´s signals, so why Captain Edward John Smith would make such an error of identification remains a mystery. It is possible that he was overcome by the enormity of the disaster which faced him, or perhaps he believed that the other ship would only start to round up the lifeboats once a number of them had been launched.

Curiously, Captain Lord had, during the Boer War, demonstrated his suitability for this kind of rescue operation when he disembarked and re-embarked a large number of troops and horses in record time and without mishap. This unusual ability in a merchant navy skipper would have been well known to the management of the White Star and Leyland lines. What more natural choice could there be?

If the plan had worked, all aboard Titanic might have been saved before the ship was allowed to sink. If the collision had not occurred where, when and how it did the rendezvous would have been effected. If only First Officer Murdoch had ordered the helm put hard a-port instead of hard a-starboard then Titanic would have turned toward the waiting Californian instead of away. ´The terrible ifs accumulate´. If only Captain Lord had not dozed off in Californian´s chart room, he might have realised that something had gone wrong much earlier.

As it was, Titanic was fatally damaged in a freak accident while her officers were trying to stage a fake one. The plan, as originally conceived, was not flexible enough to take advantage of the premature damage to the ship, or even to allow a normal rescue attempt to be made by the Californian. Had Californian tried to reach the rocket firing vessel to her south, then she would have come within sight of Titanic´s signals and all might yet been well.

Well, that´s the theory by Robin Gardiner, of course the book claims to back up each of the above points with a chapter containing evidence brought forward at the two inquiries.

But does Gardiner really expect us to believe that Titanic was navigated smack bang into the stern of a waiting rescue ship? Hell, you can´t do that NOW with GPS!