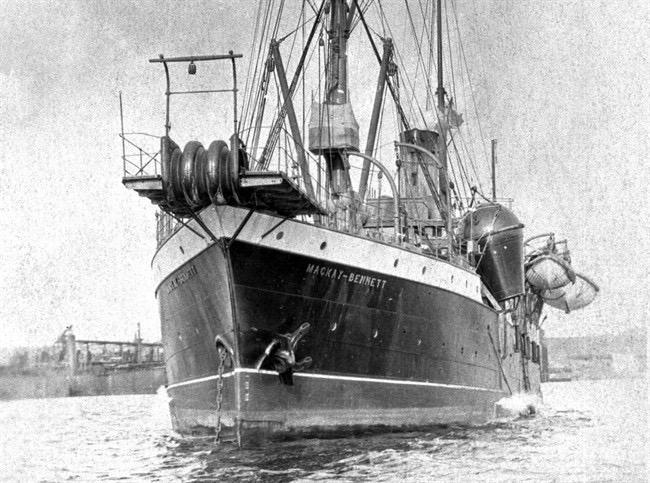

To the crew of the Mackay-Bennet, a cable laying vessel chartered by the White Star Line immediately after the disaster, went the horrific job of recovering as many bodies as was possible from the North Atlantic. All of them volunteering for the harrowing task ahead, they would be paid double for the voyage that lay before them. This had to be done as quickly as possible, too, for a number of different reasons.

Firstly, most of the bodies would still be more or less grouped together in the North Atlantic, making it easier to recover more victims. Various ships had observed bodies and wreckage, and if these were to reach the Gulf Stream, then they would be swept away, probably without trace. Secondly, a human body doesn’t fare too well out in the open sea, attacks from birds and sea creatures could make a body impossible to identify. Thirdly, loved ones and families needed to pay their respects, and the sooner the destiny of their dead was realised, then the appropriate funeral or service could be arranged.

The Nova Scotia city of Halifax would be the center of the operation to recover the dead from the Atlantic, and to meet the enormous task that lay ahead, John Snow and Company Ltd, the area’s largest funeral directors, were brought in to oversee the funeral arrangements, who in turn enrolled the help of forty members of the Funeral Directors’ Association of the Maritime Provinces to assist with the recovery of the dead.

Under the command of her Master, Captain Lardner, the Mackay-Bennet set sail from Halifax on Wednesday 17th April, heading for an area of the North Atlantic that many vessels had reported seeing bodies or wreckage in. Arriving at this location on the evening of Saturday 20th April, the crew prepared to begin the recovery operation the next morning.

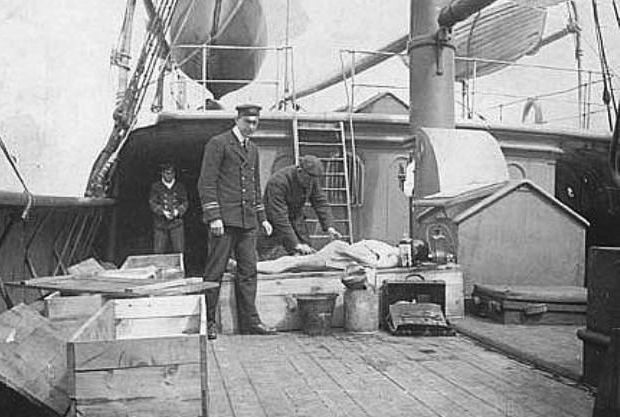

Despite a large swell which made recovery operations difficult, the crew of the Mackay-Bennet managed to recover 51 bodies. Of these 51 bodies, 24 were considered to be so badly disfigured by the sinking and the sea-life, therefore making identification impossible, that they were recommitted to the sea the same evening, wrapped in canvas sheeting, and weighed down with cast iron bars. The remainder of the bodies were embalmed and placed in coffins.

Almost one week later, on Tuesday 26th April, the Mackay-Bennet had 190 bodies on board. A further 116 had been recommitted to the sea. Desperately overwhelmed by the sheer numbers, Mackay-Bennet began to make her way back to Halifax. In the meantime, another cable ship, the Minia, had arrived to help the Mackay-Bennet in her gruesome task. One of her boats can be seen recovering a body, complete with life jacket. She would find a further 17 bodies before her Captain ordered her back to Halifax too.

The Montmagny was also added to search, as the number of bodies so far recovered was so disappointingly low. She managed to find only 3 more bodies.

The last body recovered from the water was that of James McGrady, a saloon steward from the victualing crew. His body was found by yet another vessel that White Star had chartered, the Algerine. Finally, almost one month after the disaster, Oceanic, whilst on a transatlantic crossing, came across Collapsible A which contained a further 3 bodies.

In Halifax, preparations for receiving Titanic’s dead involved turning the city’s Mayflower Curling Rink into a temporary morgue. As the bodies had been taken on board the Mackay-Bennet, each one had had a label bearing a number attached to it. Any possessions found on the body would be placed in a small bag, bearing the same number. This was to make identification easier, and to make sure that there could be no administrative mistakes at such a sensitive time.

Three different cemeteries in the city of Halifax offered a final resting place to the victims, and, based upon relative’s wishes, the bodies were interred at the Fairview Lawn Cemetery the Baron de Hirsch Cemetery, or the Mount Olivet Cemetery. The burials began on Friday 3rd May, and many of the people of Halifax would attend to offer sympathy to these unfortunate souls, buried so far away from homes and their families.

Despite the combined efforts of the authorities in Halifax and the White Star Line, about half of the 150 people who were buried in Halifax remained unidentified. The first line on these people’s headstones was therefore left blank, with just the body number engraved on the stone for reference, in the hope that one day the body would be identified. Sadly, none of these poor souls would be identified.

One funeral would bring the true depth of the disaster home to many people. The crew of the Mackay-Bennet had recovered the small body of a little fair-haired boy, and with nothing to identify him as you could an adult such as a wallet or a driving licence, he remained unidentified. The authorities in Halifax were overwhelmed with offers from people wanting to sponsor the toddler’s funeral, and provide a headstone to mark his grave. The difficult task of selecting the sponsor was made a whole lot easier when Captain Lardner and the crew of the Mackay-Bennet offered to sponsor his service. His epitaph reads, ‘Erected to the Memory of an Unknown Child Whose Remains Were Recovered after the Disaster to the Titanic, April 15, 1912.’

N.B. The child in the grave was positively-identified by DNA sampling in 2002, and you can read more about the process of identification here.