On 1st July, 1985, a combined collection of scientists from Woods Hole Deep Submergence Lab (D.S.L.), Massachusetts, led by Dr. Robert Ballard and the French Institute Francais de Recherche pour l’Exploitation des Mers (I.F.R.E.M.E.R.), led by Jean Jarry, prepared to locate the wreck of Titanic.

Armed with practically the most sophisticated equipment ever to set to sea, they sailed for the area of Titanic’s sinking. This was a two part mission to locate the wreck, and aboard the research vessel Le Suroit, expectation was high, despite the fact that as far as the cynical press were concerned, anybody who was out in the middle of the North Atlantic looking for the Titanic were wasting their time.

Bob Ballard had been seriously interested in finding the Titanic since 1973. He wanted to develop state-of-the-art underwater visual-imaging technology, to make deep-sea diving in submersibles a thing of the past, together with the perils that this entails. His vision of towing a collection of high-tech video equipment on the end of a cable two miles or more long would need major funding, so to attract this funding, Ballard used the Titanic as a means to an end.

In 1977, Ballard set out to locate the Titanic aboard the Alcoa Seaprobe, a drilling ship belonging to the Alcoa Aluminium Company. The equipment pod was attached to a steel pipe which was lowered through the bottom of the vessel in sixty feet sections, exactly like a drilling head on an oil rig! This was obviously slow and cumbersome in comparison to the long steel wire which Ballard envisaged would be employed one day, but at least it would enable him to test the equipment on the end of it.

Sadly, the operation came to an abrupt end when due to a mistake in the rigging of the pipe which then snapped off, the whole lot went crashing to the seabed, never to be seen again. Now, all Ballard could do was sit and watch as others took up the challenge to find Titanic. But they didn’t find her, and now, twelve years later it was Ballard’s turn to pick up where he left off, in conjunction with I.F.R.E.M.E.R.

The French research vessel Le Suroit spent ten days in the area of the sinking, towing behind her a state-of-the-art side scan sonar system, which was capable of making 3,000 feet sweeps of the ocean floor in each pass. The scientists aboard studied the print-outs from the relentless back and forth search, and yet again, Titanic remained elusive. By 7th August, the time was up – Le Suroit was required elsewhere. The Americans, together with a handful of French scientists, transferred to the Woods Hole research vessel Knorr. After a classified detour to photograph and film the remains of the US Navy nuclear submarine Scorpion, on behalf of the Navy, who were funding this technology, the Knorr continued to the area of the sinking.

Arriving in the area of Titanic’s sinking on 22nd August, 1985, Knorr, and the scientists aboard her, continued to search where Le Suroit had earlier left-off. The search technique employed was different from Le Suroit’s sonar sweeping, with a sled-like device called ‘Argo’, which was laden with TV cameras and towed just above the seabed, two-and-a-half miles below, looking for debris from the wreck, rather than the ship itself. The pictures sent back to the ship were seen ‘live’ from a small booth on the Knorr, watched for hours on end by the ever alert scientists. Despite suffering some nerve-jangling technical problems, the search settled down into the relentless back-and-forth sweeps of the ocean floor, known as ‘mowing the lawn’.

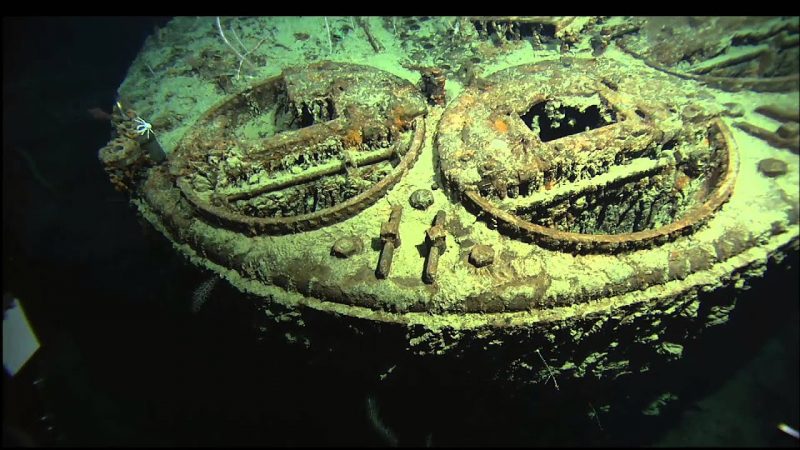

Early in the morning of 1st September 1985, the bottom of the seabed looked to be a little different from usual – instead of the usual curves and ripples of the never-ending mud and sand, unusual marks, coupled with small chunks of what were obviously man-made debris began to appear before the amazed scientists glued to the screens. Before long, larger items hove into view, including a massive ship’s boiler. The Titanic, elusive for so long, and considered to be always a part of the past, was now a part of the present.

On board the Knorr at the time of the discovery was the renowned maritime artist Ken Marschall. Once back on dry land, it was his job to try and picture the ship as it now sits on the bottom of the Atlantic, using video evidence, together with photographic evidence collated from the thousands of pictures snapped by Argo. It is his unbelievable work along with many other fantastic paintings of Titanic, some pictured before the sinking. He is also responsible for some fine paintings of the Lusitania, commissioned after Ballard toured the wreck off the coast of Ireland.

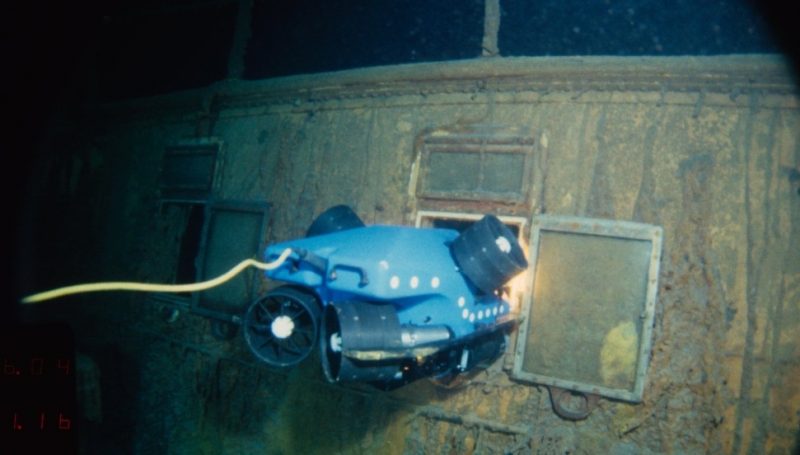

Twelve months later, Ballard and his crew returned to the wreck site, this time accompanied by a deep-sea submersible called Alvin, and a remotely operated underwater robot called Jason Junior, or JJ. Their surface vessel this time was Atlantis II, and on the evening of July 12th 1986, Ballard and his staff of about 50 scientists and crew arrived at the site.

Early the next morning (my 19th Birthday!), Alvin was brought out of its hangar on the stern of the Atlantis II to be readied for the first dive on the wreck of Titanic. At just after 8.30am, the submersible began its slow journey to the wrecked liner lying 2.5 miles below. Inside the sub were Robert Ballard, Alvin’s chief pilot Ralph Hollis, and co-pilot Dudley Foster. For two-and-a-half hours the sub plummeted deeper and deeper into the Atlantic ocean, their instruments eventually telling them that the sea floor was about 600 feet below them.

Crucial sonar equipment failed to work, and although the occupants of the sub knew that they must be pretty close to Titanic, they had to guess the general direction to head in. Eventually, the surface ship managed to point the sub in the right direction, although an alarm had begun to sound warning that one of the batteries was now shorting, meaning that their time spent on the bottom would be very brief.

Suddenly, Ballard saw the ship’s hull. “Directly in front of us was an apparently endless slab of black steel rising out of the bottom – the massive hull of the Titanic.” But the euphoria was short-lived – almost immediately after coming so close to the Titanic, Ralph Hollis was forced to head the sub back to the surface, for there were many problems to keep the sub’s crew busy through the night ahead.

The next day, Alvin returned to the seabed. Ballard’s view of Titanic this time would be amazing. As the sub inched slowly across the mud towards the ship, he glimpsed the bow looming out of the darkness. Ballard’s first instinct was that the Titanic was ‘coming right at us’. But on closer inspection, the crew of the sub could see that Titanic’s bow was up to the anchors in the soft mud.