Olympic’s keel, yard No. 400, was laid towards the end of 1908, and just over three months later, the keel of Titanic , No. 401, was laid alongside, under the massive Arrol Gantry at Harland & Wolff’s yard in Belfast. With a construction period of about three years, the two liners’ massive hulls became almost a part of the skyline on the River Lagan.

There were many subtle differences between Olympic and Titanic, and eventually between Olympic and Britannic too. The most obvious of these alterations was the enclosure of the forward part of the promenade on Titanic’s ‘A’ deck.

This modification visually set Olympic and Titanic apart from each other, making each vessel appear unique, even from quite a distance. Most of Britannic’s alterations would come as a result of Titanic’s sinking, and these included a double skin, which added an additional two feet to her beam, a deeper double bottom, and the extension of the watertight compartments higher up into the ship.

There was also a great amount of extra plating and riveting in weaker areas of the hull, and the lifeboat davits were larger, allowing more lifeboats to be carried, which in turn meant that everybody on board could be seated in a lifeboat, should the need arise.

Around the same time that the giant liners were conceived, there was a revolution in marine power under way as the steam turbine began to make its mark in commercial and naval shipbuilding. The White Star Line’s biggest rival, Cunard, had built the liners Mauretania & Lusitaniawith state-of-the-art all-turbine drive, and one may wonder why the newer White Star Line vessels were not similarly equipped.

The reason was simple: Cunard had been assisted in the two liners’ construction by the British Government, both financially and technically, and as a result of this help, much naval experience was built into the Mauretania and her sister ship, including the turbine design.

Harland and Wolff were quite limited technically, with only their own experience to draw on. They were aware of the power and economy the turbine offered, although still unsure of its reliability, and chose to play it safe by installing the originally envisaged two reciprocating steam engines driving the port and starboard triple-bladed wing propellers, with a 16,000hp centre-line steam turbine driving a four-bladed propeller using the exhaust steam from the two huge reciprocating engines.

These incredible four-cylinder triple-expansion engines weighed approximately 1,000 tons each, and stood more than 30 feet high. They were designed to create 15,000hp at 75rpm.

Supplying the incredible amount of steam required to power Titanic’s mighty engines were 29 triple furnace Scotch type boilers, 25 of which were double ended, the remaining four being single ended. This means that there were an incredible 162 individual furnaces turning water to steam to power the ship’s engines and ancillary equipment!

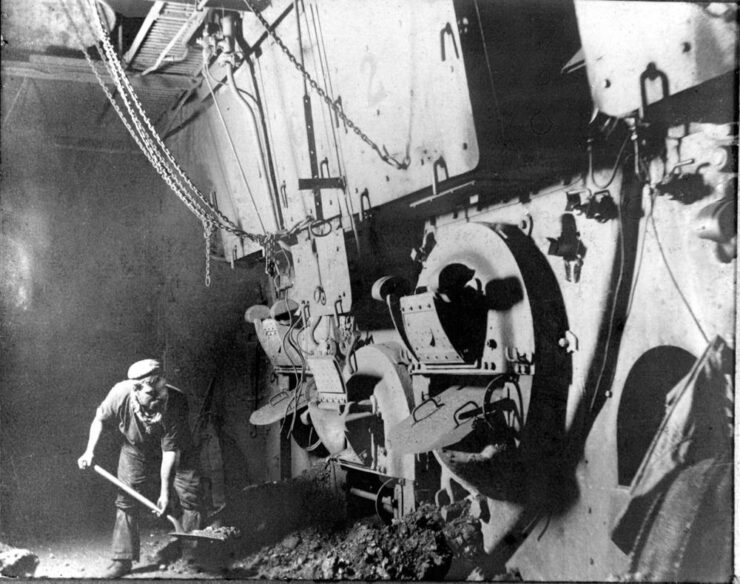

These boilers were constantly being fed coal, and Titanic carried over 160 firemen working in shifts to carry out the job, burning over 600 tons of coal per day on a typical crossing. Trimmers dug the coal out of the ship’s bunkers, wheel-barrowed it across the boiler-room and dumped it on the steel floor against the boiler. It was then shoveled into the furnace by the firemen, or stokers.

The photograph above depicts a boiler-room similar in size to that of an Olympic-class liner. There is a small pile of coal on the floor, from which the fireman can be seen to be feeding the three furnaces.

The working conditions in a boiler-room could be absolutely terrible, and even on a cold winter’s voyage, the heat could be almost overwhelming.