Titanic’s fitting out at Harland and Wolff was now complete, and the next stage in her tragically-short life would be her sea trials. These were actually scheduled for 10.00am on Monday, 1st April, a mere 9 days before she was due to leave Southampton on her maiden voyage, but due to the adverse weather conditions which would have made sailing her down the narrow channel of the River Lagan pretty hazardous, the trials were reluctantly postponed until the following day. It meant that there would be one day less in Southampton to stock the ship with all of her provisions, but it wasn’t bad news for everybody. Many of the crew, both officers and engineers, saw it as a great chance to get to know more of this mammoth ship.

Tuesday April 2nd dawned, and the weather was clear enough to undertake the trials. Crowds began to gather on the banks of the river to witness Titanic’s grand passage.

Aboard Titanic were 78 members of her ‘black gang’; stokers, greasers and firemen. There were also a further 41 members of crew which included officers, senior crewmen, cooks and storekeepers, although intriguingly, none of the domestic staff appear on the ship’s signing-on logs. Also aboard were representatives of the various companies: Harold A. Sanderson was aboard on behalf of I.M.M., Thomas Andrews and Edward Wilding were aboard on behalf of Harland and Wolff.

Missing was Bruce Ismay, and Lord Pirrie could not make it because of illness. The two Marconi radio operators were also aboard. Jack Phillips and Harold Sydney Bride were not only there to keep Titanic in touch with the rest of the world, but there was also some fine tuning of the Marconi equipment to be done. Also testing the ship’s equipment were several employees of Messrs. C.J. Smith of Southampton, who had provided the compasses for the ship, and had to ensure that they were set-up correctly. Finally, a very important man indeed had to be present: Mr. Carruthers was the Board of Trade surveyor who had to see that everything worked, and that the ship was fit to carry passengers. If all was well, he would sign a certificate, ‘An Agreement and Account of Voyages and Crew’, valid for twelve months.

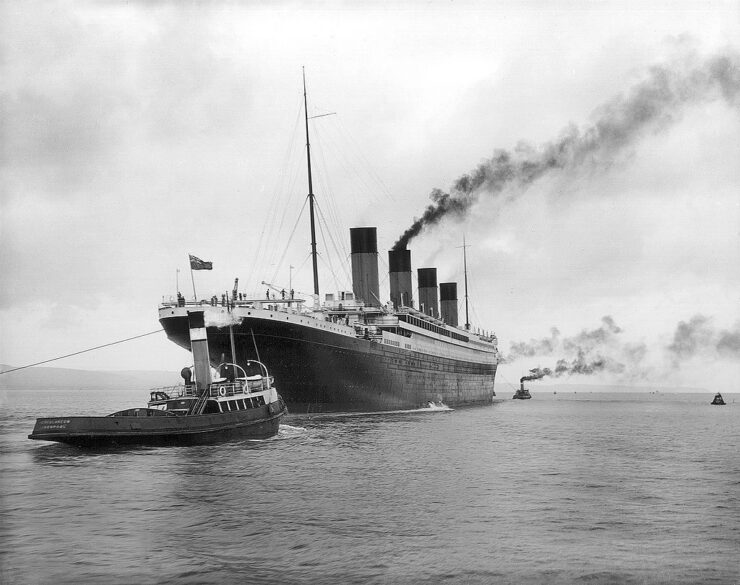

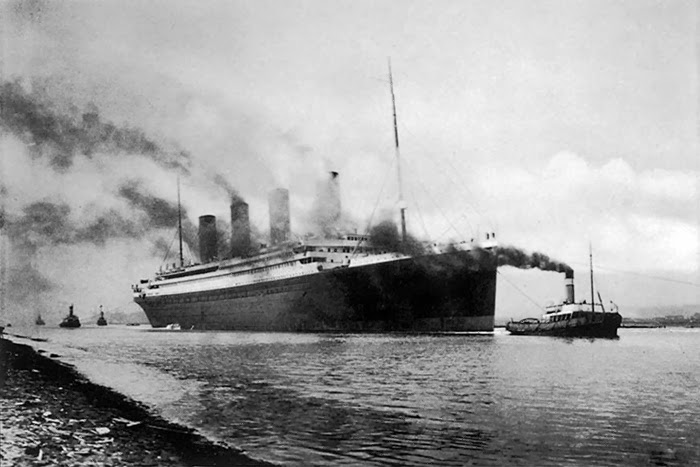

Shortly before 6.00am, the tugs that would guide Titanic from her berth and into open water arrived. Harland and Wolff’s own yard tug, Hercules, was given the honour of getting the first line aboard. The other tugs took up their positions too; Huskisson at the port side of the stern, Herculaneum at the starboard side of the stern. Hornby was stationed on the starboard bowline, whilst Herald pulled the forward line.

Titanic’s mooring lines were dropped, and on a whistle from the main tug, they all began to take up the slack in the ropes. She began to move away from the jetty, and soon lay in the middle of the river, waiting to move further. She made her way down the river, passing the crowds cheering and waving from the banks, glad that they had witnessed this leviathan progressing gracefully down the Lough.

She proceeded down the Belfast Lough, as seen in these two beautifully atmospheric photographs, until she was only 2 miles off Carrickfergus, still with the tugs providing the power. But the time had come to detach the tugs. They all stopped, casting off their lines. and stood clear of the massive liner.

A rush of excitement passed through everybody as a blue and white burgee was raised: ‘I am undergoing speed trials’. The bells of the telegraph ran out across the bridge, and was repeated deep down in the engine-room. It was the moment of truth! As the valves were opened allowing the steam to travel from the boilers to the two huge engines, Titanic’s propellers began to turn, slowly, but surely. There was no mistaking the turbulence in the water at the stern, and the ship began to move under its own power for the very first time!

Cautiously at first, but then faster and faster, Titanic was worked-up to about 20 knots. Upon an order from the bridge, Titanic’s engines were stopped, and she was allowed to drift to a stop. Several more manourvres were called for, including turning using only the rudder, turning using only the propellers, and several start-stop tests. Just before lunch, there was another test to perform: while the ship was traveling straight ahead, the wheel was ordered hard over. The circle Titanic travelled had a diameter of 3,850 yards.

Following a hearty lunch, there was yet another task to conduct, this time a major stopping test. A buoy was dropped in the water, and Titanic turned and ran at full speed towards it. When the vessel was alongside the buoy, Officers Moody and Murdoch observed the position of the buoy through their sextants, and the engines of the ship were put ‘full astern’. When Titanic came to a dead stop, she had taken about 850 yards to come to rest. All the while, Mr. Carruthers and various representitives were jotting down the results of all of the tests, and comparing notes and data.

At 2.00p.m., Titanic was set on a straight course out into the Irish Sea, traveling for two hours and covering a distance of approximately 40 miles. She turned, traveling for yet another two hours, heading straight back down towards the Belfast Lough, putting in a few twisting port and starboard turns to test her handling as she returned to the City of her birth. At about 7.00pm, she came to a halt.

Mr. Carruthers demanded one final test – the lowering of the port and starboard anchors. This completed, he signed the certificate, together with Sanderson and Andrews, enabling Titanic to ply her trade. Anybody who was not to travel on to Southampton were ferried ashore, including Harland and Wolff staff, and Mr. Carruthers, the Board of Trade surveyor.

At about 8.00pm, Titanic departed for Southampton. Speed was of the essence now, as she had to arrive in Southampton on Wednesday’s midnight tide. Titanic wheeled around, using her propellers to turn, and began to leave Belfast. This time, it would be forever.

After an uneventful near 600 mile voyage to Southampton, she was met by five tugs of the Red Funnel Line, Ajax, Hector, Vulcan, Neptune and Hercules. They all combined to warp Titanic efficiently into Berth 44, the place where she would depart from in a little under 7 days.