Titanic was now ready to travel. The crew were all aboard, save for a couple of thirsty firemen enjoying a last-minute pint in one of Southampton’s many public houses who would miss the departure. Luckily, there were spare members of crew on standby ready for this very situation, which obviously occurred on a regular basis, and they were duly ‘signed on’, the remaining spare crew would be taken off aboard a small vessel further down the river together with the Southampton pilot. ( Titanic Passengers Embarked Southampton )

The passengers were all aboard, the majority of them at the port-side rails bidding farewell to friends and families. Many people, especially those in Third Class, or ‘steerage’, would be making a one-way journey, looking for a better life in America, the so-called ‘New World’. They had sold everything they owned, which for many of them wasn’t a great deal to begin with. Their worldly belongings would fill just a couple of bags, or maybe a steamer trunk in some cases.

But for the wealthier people aboard in the First Class accommodation, of which there were many, this was merely a pleasure trip, a society outing. The maiden voyage of the world’s biggest and grandest vessel would be a major addition to one’s social Curriculum Vitae. Old friendships would be rekindled, and more importantly, new friendships and contacts would be formed and developed.

The pilot, George Bowyer was now aboard, a familiar face to Captain Smith and most of the officers. It was Pilot Bowyer who had been on duty the day Olympic had collided with HMS Hawke, and Smith had been the master that day too. To complicate matters, George Bowyer looked uncannily similar to Captain Smith, and anyone seeing Bowyer from a distance might have thought that it was Smith!

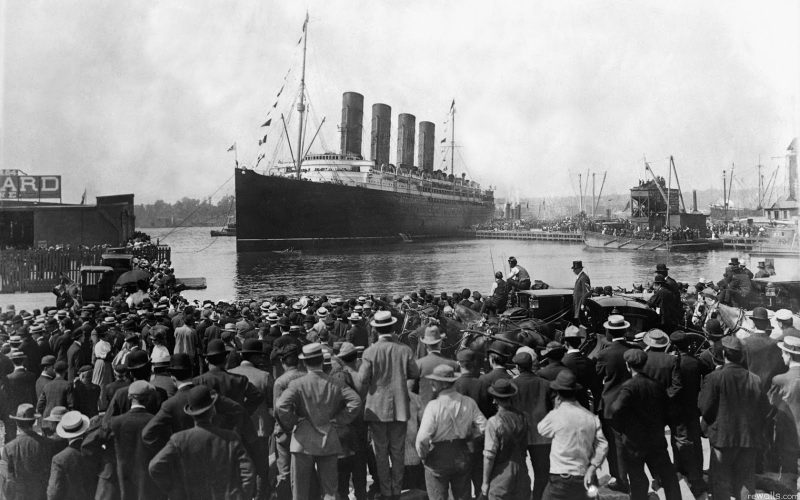

Just before noon, on the 10th April, 1912, the Blue Peter pennant, indicating ‘Imminent Departure’, was run up Titanic’s foremast. The throaty triple-valve whistles were heard three times right across Southampton. The tugs were all in place to nudge and heave at the mass of the hull, until such time that Titanic’s mighty engines could turn the propellers out in open water.

The lines holding the enormous liner against the dock were cast off, and the five comparatively tiny tugs began their heavy work. Pushing and pulling at the massive hull, constantly in touch with each other by a series of whistles, the tugs were working hard. But once out in the River Test, upon which Southampton is built, the tugs dropped all of their lines. Titanic’s telegraph rang out, and the mighty engines started to turn the propellers. The voyage had begun.

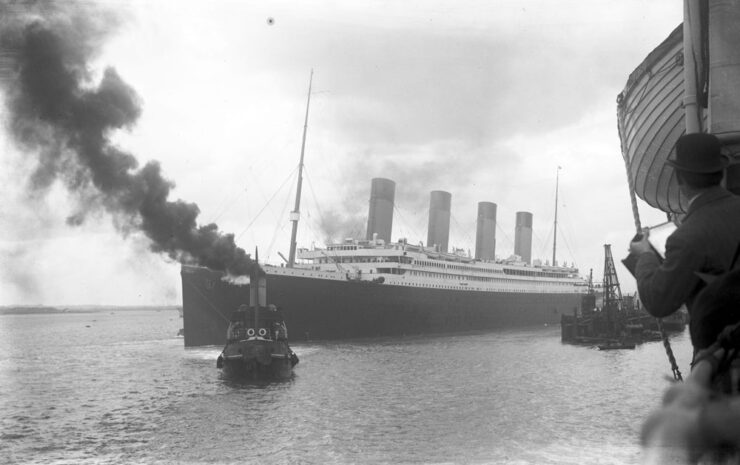

As the giant liner made her graceful way down the river, the turbulence created by the massive hull was causing problems. Two liners were moored in tandem alongside their pier, the Oceanic was inboard, and the New York was on the outside. As the huge volume of water displaced by Titanic came upon these two ships, the New York rose high in the water, then dropped back down with enough power to snap her mooring lines like string.

The stern of the New York, which was unmanned, began to swing out into the river, and towards the Titanic, pictured here on the left. The Captain of the tug Vulcan, in the centre of the photograph, managed to get a line aboard the runaway, and aboard Titanic , Captain Smith ordered ‘Full Astern’, to lessen the drawing effect the Titanic was having on the New York. The two vessels came within four feet of each other, the distance between your outstretched arms! Disaster had been very narrowly averted.

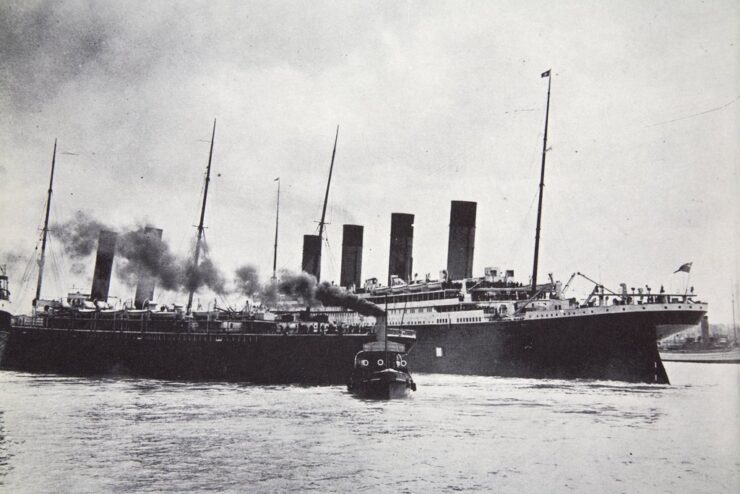

With that little drama out of the way, Titanic steamed on, out of Southampton Water, with the tiny Isle of Wight on the starboard side. Her next stop, at Cherbourg, was approximately 70 miles away. A further 274 passengers would board here, but Titanic was far too large to fit in Cherbourg’s tiny port. The passengers, together with all of their luggage, would be ferried to the mighty liner aboard two specially constructed White Star Line tenders, Nomadic, seen here on the left, and Traffic along with a large quantity of mailbags.

One-and-a-half hours after she dropped anchor in the Cherbourg roadstead, Titanic was ready for departure again, and this time the Irish town of Queenstown would be her next, and final, port of call. ( Titanic Passengers and Crew Embarked Cherbourg )

Queenstown was reached early the next morning, and by 11.30am, she was anchored a couple of miles offshore. Once again, two small White Star Line tenders, America & Ireland, ferried the passengers, their luggage and the mail to and from the ship. Also aboard, hiding under the mailbags, was one of Titanic’s fireman, John Coffey, who’s home was listed as Queenstown on the crew’s signing on sheets. He came ashore, and must have felt like the luckiest men in the world when the reports of Titanic’s demise began to filter through only days later. (Titanic Passengers and Crew Embarked Queenstown)

Now, with Queenstown and the Irish coast rapidly fading on the horizon, Titanic moved out into the open waters of the Atlantic Ocean. The crew and officers could now begin to get into their routines and watches, and the passengers now had time to explore the great liner, meet old cruising friends, or organise parties for the rich and the famous.

Almost everybody would now know how to find their cabins, but a few would still get confused by the labyrinthine corridors, and have to rely on a harassed, but helpful steward for directions, even though they too had only a sketchy knowledge themselves of the seemingly never-ending interior of the brand new ship. It was a learning process for even the most experienced crew, but no doubt they would be more confident on the return journey.

As the days of the voyage passed, Titanic sped steadily westwards, towards her next port of call, New York. From leaving Queenstown, to noon on Sunday 14th April, Titanic had put some 1,500 miles behind her. She was almost constantly receiving warnings from other vessels who had encountered the ice, but would her crew, especially her experienced Captain, take heed?