The Olympic-class liners were designed to rival the Cunard Line’s greyhound steamers Mauretania and Lusitania, however, there was one vital area where the Olympic-class liners lagged far behind the state-of-the-art Cunard sisters – speed.

Cunard had borrowed money at very favourable rates from the U.K. Government to enable them to design and build the two ships, and they incorporated into the design the latest technology that would allow them to win back the coveted Blue Riband. This included four steam turbines driving four propellers, giving great speed in return for very good economy.

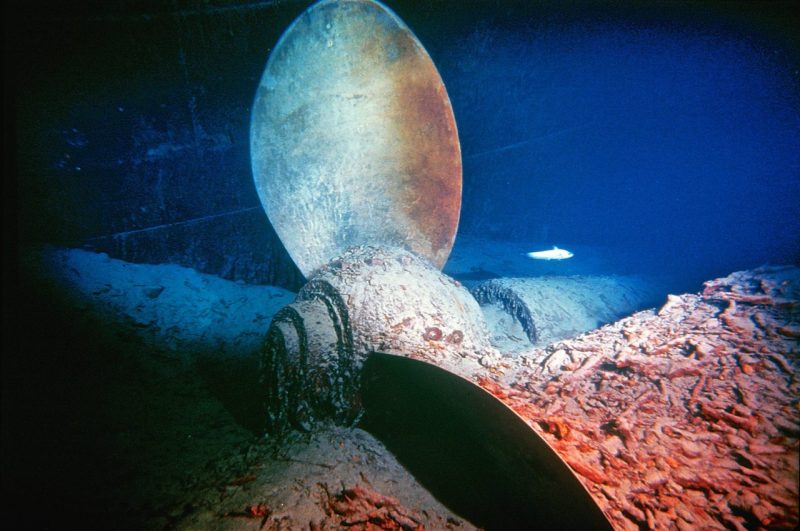

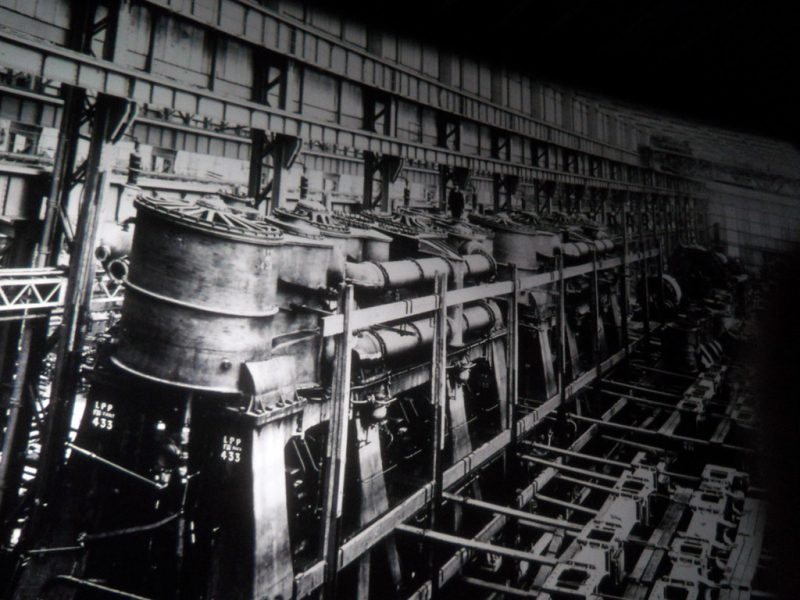

The Olympic-class liners had a system of propulsion which was really a compromise between the old way and the new. This system comprised of two three-bladed wing propellers each independently driven by a four cylinder triple expansion reciprocating steam engine, and a four-blade center propeller which was driven by a small low-pressure steam turbine using exhaust steam from the two main engines. The center propeller was made from manganese bronze, and cast in one piece, whereas the two outer propellers were cast in sections. The weight of the outer propellers was about 38 tons, whilst the smaller center prop. weighed in at 22 tons.

Contrary to what was depicted on James Cameron’s movie Titanic, the center propeller could only be cut-in once the steam from the two outer engines could be guaranteed to be ‘dry’, and this usually translated into a mile or two away from port or shore. This turbine was also non-reversible.

Below is picture of Titanic’s starboard propeller as it looked during a photographic expedition to the wreck-site in 2000. The propellers look to be in very good condition, which is hardly surprising considering that they are made from manganese-bronze, and in fact will probably last an incredibly long time, much much longer than the rest of the ship, although they might get buried if and when the stern collapses on top of them.