- Builder: Harland and Wolff

- Yard No.: 333

- Launched: 1900

- Maiden Voyage: 1901 Liverpool – Cape Town – Sydney

- Gross Tonnage: 12,531 tons

- Length: 550.2ft

- Beam: 63.3ft

- Decks: 3

- Funnels: 1

- Masts: 4

- Propellers: 2

- Engines: 2 x four cylinder quadruple expansion

- Boilers: 4 double ended + 1 single

- Speed: 14 knots

- Port of Registry: Liverpool

- Carrying Capacity: 400 passengers, 100,000 refrigerated carcasses

- Sister Ships: Afric, Medic, Persic, Runic II (Jubilee Class Liners)

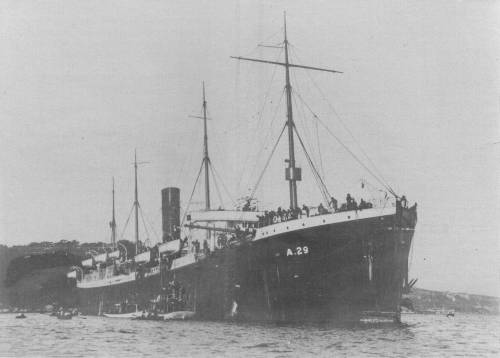

Suevic was the fifth, and final, member of the Jubilee-class liners designed specifically for the White Star Line’s Australian run, the other four being Afric, Medic, Persic and Runic II. Her large refrigerated cargo holds made her the ideal vessel for transporting perishable goods on this route.

She entered into White Star Line service on 9th March 1901, but it wasn’t long before she was requisitioned for use as a troopship, carrying soldiers to Cape Town to fight in the Boer War.

By 1902, Suevic was solely employed on the Australian run, and it was whilst returning from there in 1907 that led, eventually, to one of the most remarkable events in White Star Line history.

On February 2nd, 1907, she left Melbourne under command of her master, Captain Thomas Jones, and was due to call at Cape Town, Tenerife, Plymouth, London and finally Liverpool. She carried 382 passengers, 141 crew, and her holds she carried various items of cargo which included thousands of sheep carcasses to the value of £400,000.

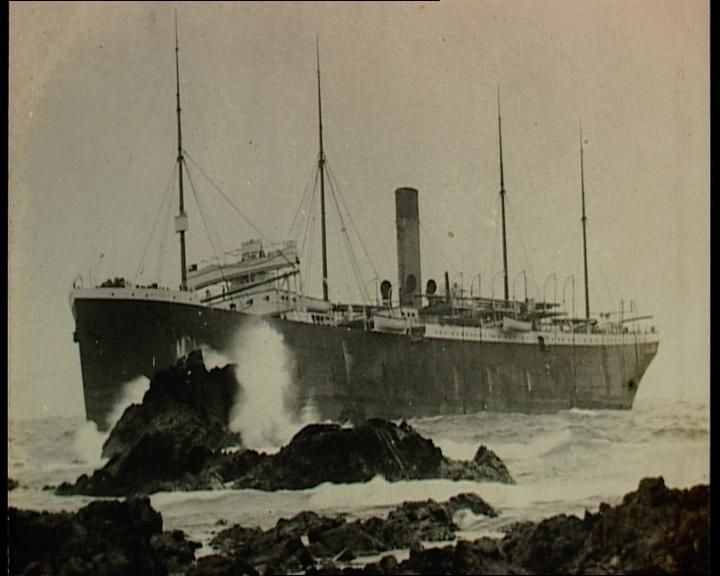

By noon on the 17th March, Suevic was about 140 miles from the Lizard on the Southwest coast of England, a notorious danger spot for shipping for centuries before. Of course the normal procedure for all shipping was to keep well-clear of this treacherous area, however, because of a fog that now enveloped Suevic, the crew could not work out the ship’s position, so the next choice open to them was to fix the vessel’s position using the light from the Lizard lighthouse. This was spotted just after 10.00pm later that day.

Suevic’s officers believed that they were 10 miles or more away from the Lizard, and then made two terrible mistakes. Firstly, they carried-on at full speed, and secondly, they did not use the ship’s sounding line, a lead weight on a marked rope, which tells the user how deep the water below the ship is.

The officers’ estimates of how far away the light was were to be proved drastically wrong, as twenty minutes after sighting the light, Suevic hit the Maenheere Rocks at full speed, only a quarter-of-a-mile from the Lizard. Her bow was seriously damaged, but the mid section and stern, together with the boiler-rooms and the engines, was relatively intact.

After some initial attempts at trying to back the stricken vessel off the rocks by running both of the remarkably undamaged engines at full astern, Captain Jones ordered the firing of the ship’s distress rockets, although because of the way the ship was grounded, there seemed to be no immediate danger of the ship sinking. A local rescue effort was launched, and all of the passengers were taken ashore at daybreak the next morning. At least one of Suevic’s crew would later serve on Titanic. Stewardess Katherine Gold, 35, was also present when Olympic was in collision with HMS Hawke in 1911!

For the next nine days, various vessels were used to try to pull Suevic from her position on the Maenheere Rocks, but she was stuck firm, and the White Star Line were now faced with a stark decision. They could either abandon the six-year old vessel where she lay, or they could separate the damaged bow from the rest of the vessel and salvage the rear section, and make a new bow section. They chose the latter, and by April 2nd, the 212-foot long bow had been cut-off from the rest of the ship at a point just behind the bridge, using nothing more than carefully placed charges of dynamite. (Actually, although this sounds quite dangerous, a skilled operator could use just the right amount of charge to remove a rivet head.)

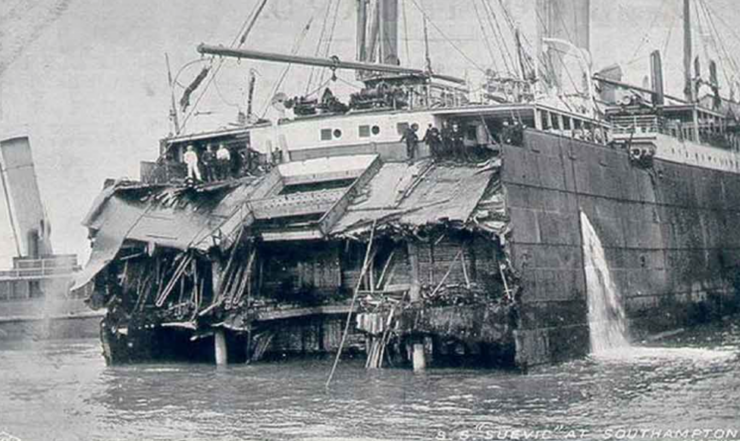

The stern was pulled away from the bow, and in a remarkable demonstration of the effectiveness of Suevic’s watertight compartments, she sailed, under her own steam, and in reverse, to Southampton, where there was a dry-dock waiting for her, although tugs were used to steer her safely.

A completely new forward hull section was fabricated at Harland and Wolff’s Belfast yard, which was towed to Southampton in the middle of October. This was moved into position on 4th November, and the relatively easy way in which the two halves were connected speaks volumes for the craftsmen of Harland and Wolff.

Suevic was jokingly awarded the title ‘Longest Ship In The World’, the reason being that ‘her bow was in Belfast, whilst her stern was in Southampton!

All of the expense and hard work was not in vain, as Suevic was a good servant to the White Star Line, and no doubt repaid the cost of her incredible repair many times over, until she was sold in October 1928 for £35,000 to a Norwegian company who converted her into a whaling factory ship and renamed her Skytteren.

Skytteren was sunk on 1st April 1942 by a German vessel whilst trying to escape to Britain.